"Most students like teachers who bring clear knowledge in a convincing, self-assured way. With statements like 'sometimes, in somehow similar positions, something like this might be a good idea' you do not make a very authoritative impression." - Willy Hendriks - Move First, Think Later*

"The Minority Attack".

Generations of chess players owe their understanding of what the minority attack is and how it works to the excellent book Simple Chess by GM Michael Stean. To quote Stean, a minority attack is 'no more or less a method of weakening an otherwise sound pawn set-up by advancing pawns at it'. Two pawns are advanced to reduce three pawns to one weak pawn, or one pawn to reduce two pawns to one weak pawn, hence 'minority' attack. According to Stean, the process of the minority attack 'is quite long and slow, the payoff at the end relatively small (one weak pawn to aim at, two maybe if you're lucky), but its value is undeniable', and 'it cannot easily rebound on you.'

What follows is a series of short articles about how the minority attack works in master chess. Contra Stean, it can easily rebound on its user (the problem resides in what we consider 'easy'), even a user as strong as World Champion Boris Spassky. The 'when?' to play the minority attack is as important as the how. And the answer is entirely context dependent: all that really matters are the specifics of the position in question.

*Move First, Think Later is worth reading. In the vein of non-chess related philosophical works about both the limits of language in helping to convey information and the limited value of rules of procedure in scientific discovery, Hendriks makes all kinds of heretical arguments in favour of questioning the received rules of good play in chess.

The Minority Attack is Not Necessarily an Easy Thing to Get Right

Q: I'm unclear, just what is the minority attack?

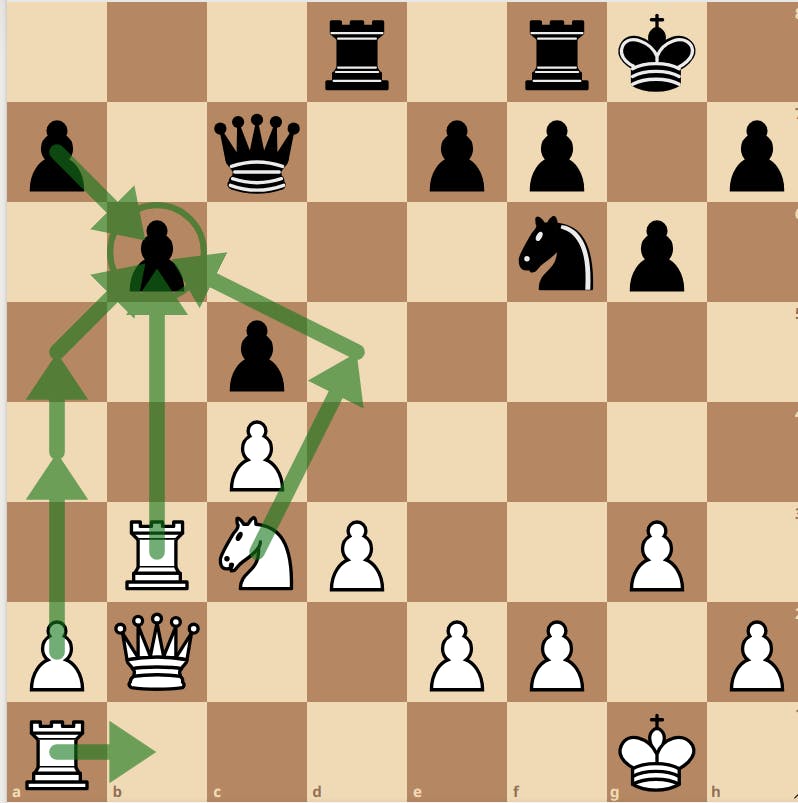

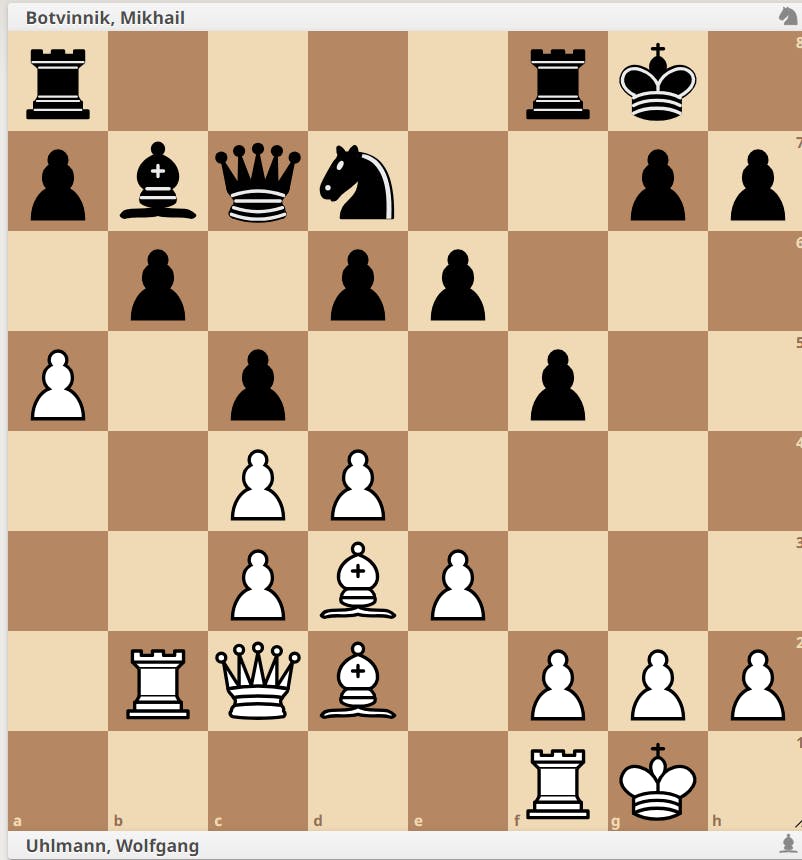

A: Here is the visual demonstration. This position is an example Stean uses to demonstrate the basic concept:

White to move

White will play a4-a5-ab, give black a backward pawn on b6, then play Rb1 and Nd5 so all five of white's pieces will be attacking the weak pawn on b6. Correspondingly, all five of black's pieces will be compelled to try and defend that point. Should black answer a5 with ba, black will have isolated pawns on a5, a7, and c5. Black will be a pawn up, but, in a sense, three pawns down, as the doubled a-pawns can be attacked by white's rooks, and the isolated c5 pawn will be a burden for the rest of the game.

White will then be free to manoeuvre to create a second weakness and thus a winning advantage elsewhere on the board (see: 'The Principle of Two Weaknesses'). Well-prosecuted games are generally won in phases: one advantage leads to another, and is then traded for a different advantage, and so on until an opponent resigns facing a quite different final threat to the one they originally faced in the first phase of their defence. The minority attack is thus a prime example of the phenomenon of the 'Transformation of Advantages'.

Now, all that is fine in theory. When theory is put into practice in a real game, ideally it might look something like the following

Emmanuel Lasker - Jose Raul Capablanca. 1921, World Championship. Game 10:

31… a5! Capablanca begins his minority attack.

Here, black wins rather easily, albeit slowly, as

32. Qb2 a4 33. Qd2 Qxd2 34. Rxd2 ab 35. ab

leaves white with two ruinously weak pawns on b3 and d4. I'd recommend playing through this game on one of the online databases, as there is plenty to be learned from here about how Capablanca makes his rook active (attacking the two weak pawns) and Lasker's rook passive (defending the two pawns). But black's structural advantage is so overwhelming that a rank amateur might win it without really knowing what they're doing. So to give this game as an archetypal example of the minority attack in practice as well as theory could be somewhat misleading.

The problem with this example from an instructional perspective is that it occurs in the final phase of the game, and the defence is in its death throes. Instead, let's look at situations you and I more commonly encounter where the minority attack is part of the opening and early middlegame. The following two examples featuring the doubled white c-pawns typical of a Nimzo-Indian. First up, as promised, is an example of the minority attack rebounding on no less a player than then World Champion Boris Spassky in his match against Bobby Fischer.

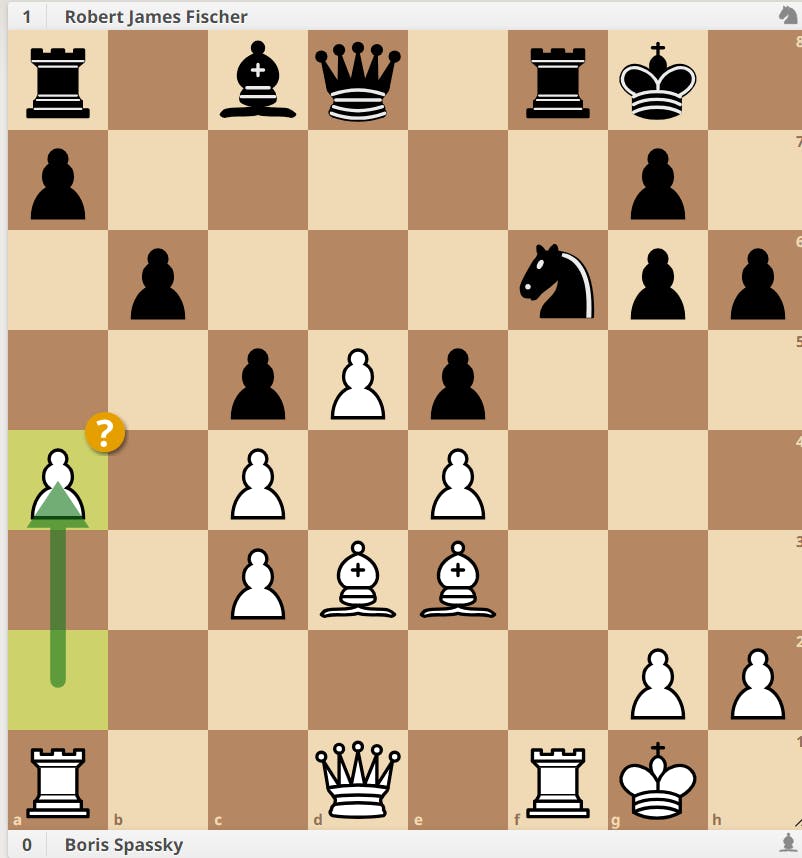

Boris Spassky - Robert James Fischer Reykjavik, 1972 World Championship, game 5:

After 16. a2-a4?

Here, the minority attack looks natural and feels automatic, but is in fact a terrible mistake. Fischer replied:

16...a5!

fixing Spassky's a-pawn as a permanent weakness. Black's corresponding backward pawn on b6 is not weak at all, as it is not vulnerable to effective attack.

How, might you ask, could a player of Spassky's stature make such a mistake? On the chess level (ignoring psychological factors), pawn play on the queenside feels natural in the position because black has good play on the kingside, and chess players are told to play on the opposite side of the board to where their opponent is playing.

Unfortunately for white, here, 16...a5 gives black a weakness to pressure on the queenside to compliment his kingside play. Consequently, and without it being obvious, black has control of the whole board, as Fischer demonstrates:

17. Rb1 Bd7

Taking aim at a4. The threat, as Nimzowitsch said, is stronger than the execution, as white is now tied down to protecting a4.

18. Rb2 Rb8 19. Rbf2 Qe7 20. Bc2

Defending a4 in the hope of setting the white queen free to wander. But it doesn't matter. The weakness is such that white is overstretched and black can turn to probing kingside and creating a second weakness there.

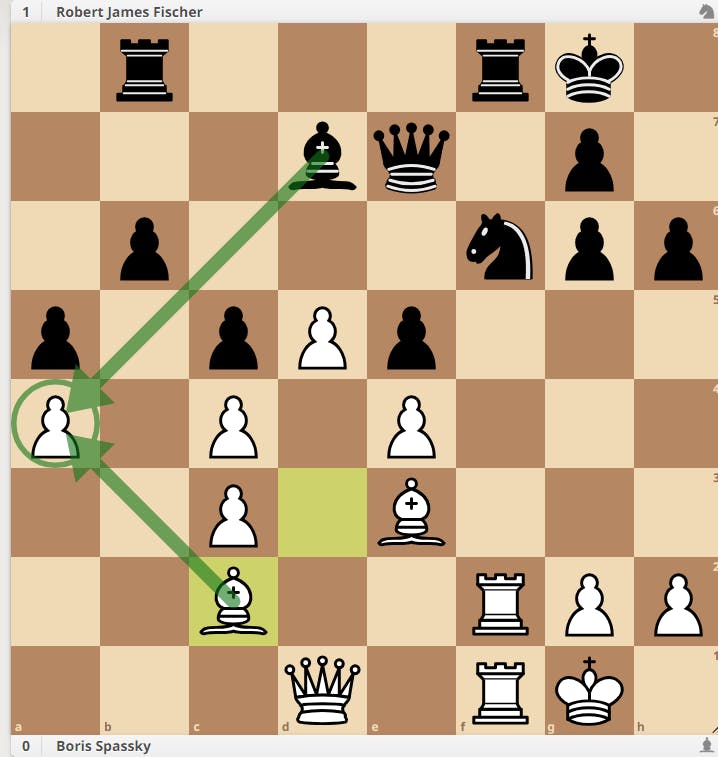

20... g5 21. Bd2 Qe8 22. Be1 Qg6 23. Qd3 Nh5 24. Rxf8+ RxR 25. Rxf8 Kxf8 26. Bd1 Nf4 27. Qc2 Bxa4! 0-1

The threat is stronger than the execution, until the execution. The queen is deflected by the capture of the very pawn white hoped to use to destabilise black's queenside. White cannot cover both the e-pawn and the resulting double attacks on g2, e1, and so resigned. A rather spectacular rebounding of a minority attack indeed!

From two World Champions to another. Here Botvinnik exploits an ill-timed minority attack.

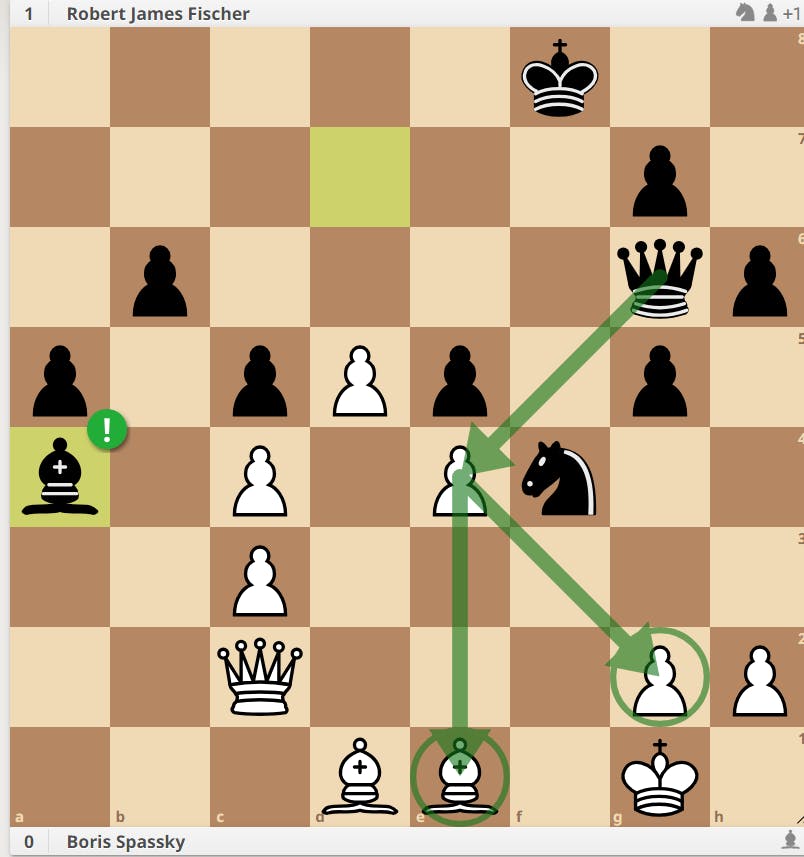

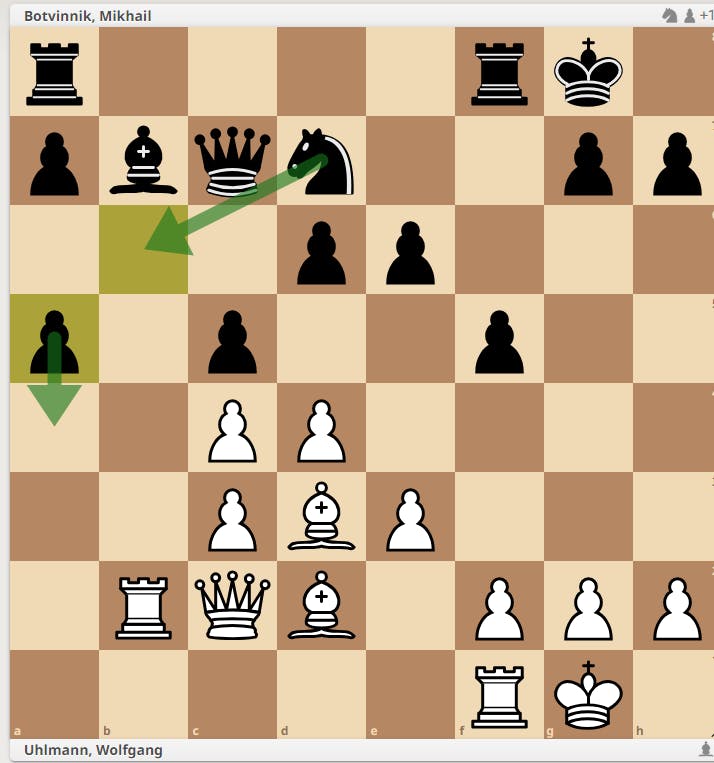

Wolfgang Uhlmann - Mikhail Botvinnik. Munich, 1958:

Black to move.

Here, white has played a4-a5 intending to leave black with a backward b-pawn on b6. Sadly for white, black played:

15... ba!

Which, in contrast to Stean's example, works here as both black's bishop (from c6) and his knight (from b6) can protect the a5 pawn when it advances to a4. Rather than a ruin of weak pawns similar to the Stean position we looked at, the placement of black's pieces instead makes his shattered queenside structure a strength. Black emerges a passed pawn up.

If Grandmasters like Spassky and Uhlmann can misplay a minority attack, then clearly its correct implementation is not an entirely trivial thing. In the next article we'll see examples where the minority attack is, regardless as to whether it is easy or difficult to play, compulsory, rather than optional.