"Chess is a mental exercise in managing failure." James Rizzitano, Understanding Your Chess

Inside the mind of the chessplayer is a laboratory mouse running a maze. He explores every avenue, usually more than once, even the blind alleys, but not necessarily with the idea of escape. He does so because he is programmed by nature to complete a circuit, regardless that parts of that circuit prove to be of no value. The mouse is a creature of habit, and the maze is as much a home as it is a prison.

We all know we're supposed to analyse our own games to get better. But the question as to how we're supposed to analyse our own games if we don't know what we're looking for is one that seems vexing in the abstract. I say in the abstract, because for most people seriously analysing their own games remains merely a proposition rather than something they actually do. Most people just let the engine do the work and draw largely false inferences from what the machine tells them (mysteriously, Stockfish usually tells them exactly what they want to hear about their own weaknesses!). The difference between seriously analysing our own games and pretending to analyse our own games lies in the search for and identification of patterns of failure. Properly analysed, your games should reveal that, like the mouse in his maze, we're repeatedly making the same mistakes - going down the same blind alleys - that have become instinctual by virtue of habit.

The epigraph at the beginning of this article, from Rizzitano's Understanding Your Chess - which along with The Road to Chess Improvement by Yermolinsky are the best works on the process of analysing your own mistakes - is prefaced by the following observation:

If you are unable to determine why you are losing games, then it is pointless to continue competing in tournaments - you are wasting your time. Every game should be used as an opportunity to learn from your mistakes and as a mental reminder to avoid repeating these errors in the future. Losing a game because of an unknown idea is a learning process - losing multiple games in a similar manner is a bad habit to be avoided.

And yet, guaranteed, we all exhibit this bad habit. All of us. Each of us has our favourite mistakes that, whether we realise it or not (and many, preferring not to think seriously about painful defeat, don't), keep coming back around and around and around again to cost us points and half points. Indeed, some of us have more than one favourite mistake. Only once we identify these habitual mistakes can we struggle against the instinctual urge to make them.

To prove this point I will demonstrate the reoccurring mistakes in my own games and in those of some of my clubmates. Really, I could do this for practically every player whose games I've had the fortune to analyse. But for the purposes of brevity and force of argument I'll confine myself to just three John Littlewood CC players, from across three different rating bands, and our games from the past twelve months.

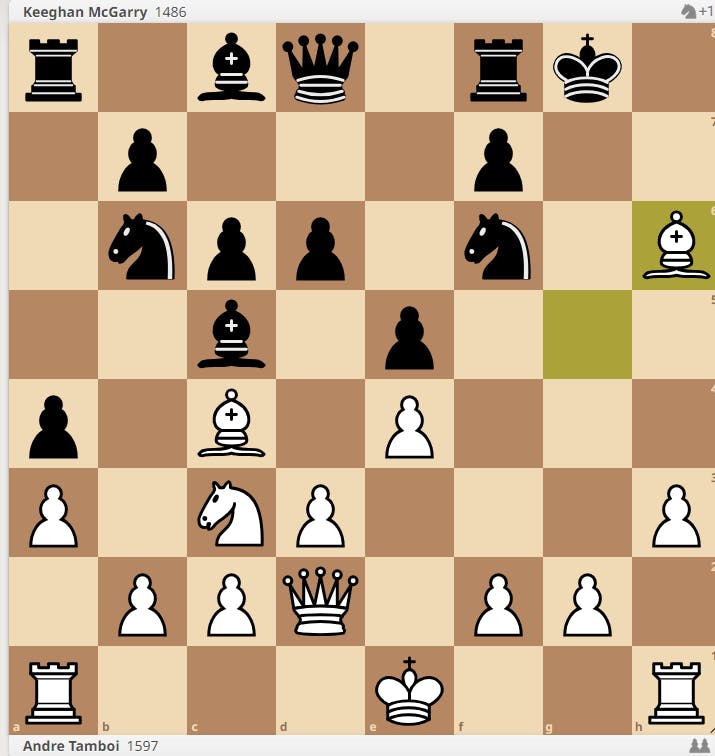

Keeghan McGarry (1486) - Charge of the Knight Brigade

Black to play. Tally ho?

Some players do not like to sit and suffer. Unfortunately, sitting and suffering is an essential part of chess. As is finding the best continuation. Our very own Keeghan McGarry is black in both of the above positions. Our man was better in the first, and up against it in the second. In the former he could have played ... Nh7!, keeping the white queen out of g5 and forcing white to play BxRf8, leaving black with a slight material edge and a large positional advantage. In the latter, he should have curled up like a tiny mammal, bristled his spines with ... g6 and endured white's attack. Instead, in both examples he played...

... Ne4??

Tally no.

Which in the first game leaves black a pawn and position down after 15. Nxe4 Nxc4 16. dxc4, and in the second game a pawn and position down after 14. Nxe4 dxe4 15 Bxe4. Different positions, same mistake, same result - the product of impatience and a desire for heroic counterattack over grim survival.

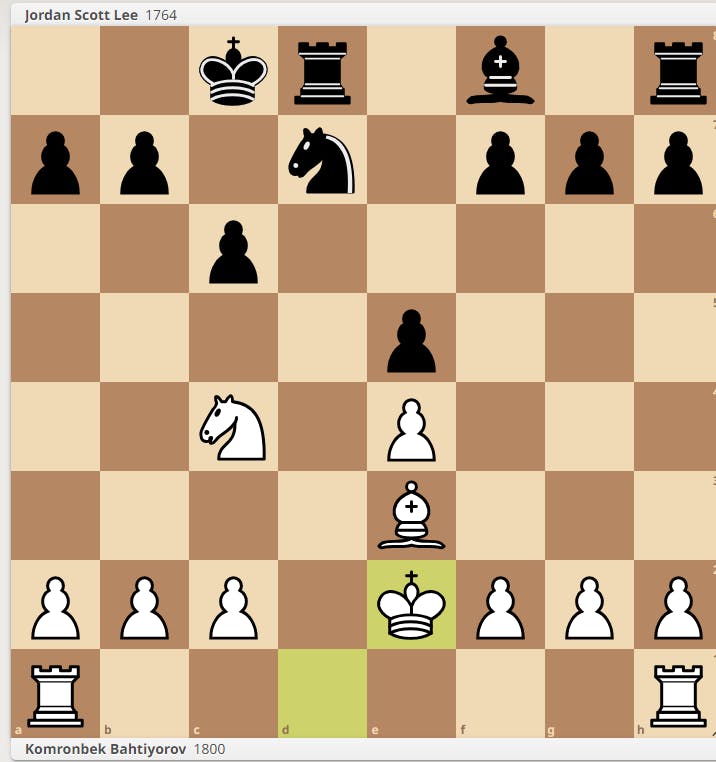

Jordan Lee (1764) - Escape to Defeat

We've all heard that in the endgame the king belongs as near to the center of the board as possible. But when does the endgame begin? (How long is a piece of string?) Well, sometimes as soon as the queens are exchanged.

Black to move.

Here, Jordan had a comfortable advantage over a slightly stronger player. He had more space and the luxury of time to decide just how he would eventually weaken white's queenside. All black had to do in the short term was connect his rooks.

14... 0-0?

Just not that way! It will now take the black three or more moves to return the king to the center where it belongs.

Compare this with a similar ending later in the season:

Black to move.

Here Jordan would be looking to equalise. Having castled queenside, his king was already more or less in the center and doing as much as it possibly could by protecting the knight on d7 and the rook on d8. 12... Bc5 now, offering the exchange of bishops, would have equalised immediately. Alas, the threat to the a7 pawn instead prompted him to move his king away from the center:

12... Kb8??

There then followed 13. Rad1 (pinning the knight) f6 (protecting the e5 pawn) 14. Rd3 (doubling the rooks) Bc5 15. Rhd1 and black should have lost material and the game:

The thread about to break.

Black has no moves. After 15... Kc7 white should have cashed in with 16. Rxd7+ RxR 17. RxR+ KxR 18. Bxc5 and a winning advantage. But didn't. But won shortly after anyway.

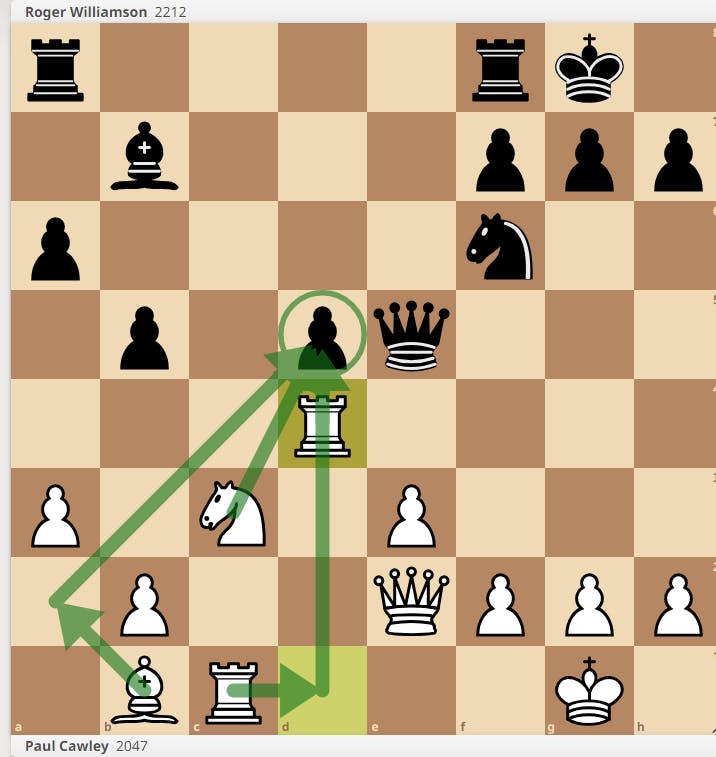

Roger Williamson (2212) - The Goalkeeper's Irrational Love of the Two-Result Position

Here I could highlight my obsession with moving my f-pawn regardless as to whether or not it's good or bad. That would be a general mistake I think most players are prey to at some time or another. Instead, I've picked something more idiosyncratic and altogether more conceptual.

When I first heard about Kasparov's 'principle of infinite resistance' it was love at first sound. If one of the greatest of world champions says you don't have to lose bad positions, that by adopting an attitude of sheer determination you can usually save them, then pass me the spade and sandbags. However, as healthy as such an attitude is, when - like anything else - taken too far it becomes perverse.

Over the past two years I have become aware that as black I've developed a tendency to abandon my cursory search for the best move in a position in favour of the move that will allow me to prove my Kasparov-like determination not to lose. But by doing so I just as frequently renounce all hope of winning. In the sense that I am no longer responding to the position, and instead enacting a story of heroics best left in my head, this is the flipside of Keeghan's refusal to go to the trenches.

Black breaks too soon.

Stockfish prefers 17... Rfc8 and keeping the tension to 17... e5?! as played. After the game move, the forcing sequence 18. dxe5 Nxe5 19. Nxe5 Qxe5 20. Rd4 leaves black with no pawn breaks/levers, and thus no means of changing the nature of the game.

Black must suffer.

Black, by which I mean me, must sit there without any active prospects, restricted only to anticipating and preventing white's means of trying to exploit the isolated d5 pawn (pictured). Which is possible. But against a much higher rated opponent would have ultimately proven a fruitless task.

This is the very definition of a 'two-result position': one side, white, either wins or draws. He cannot lose. And black cannot win.

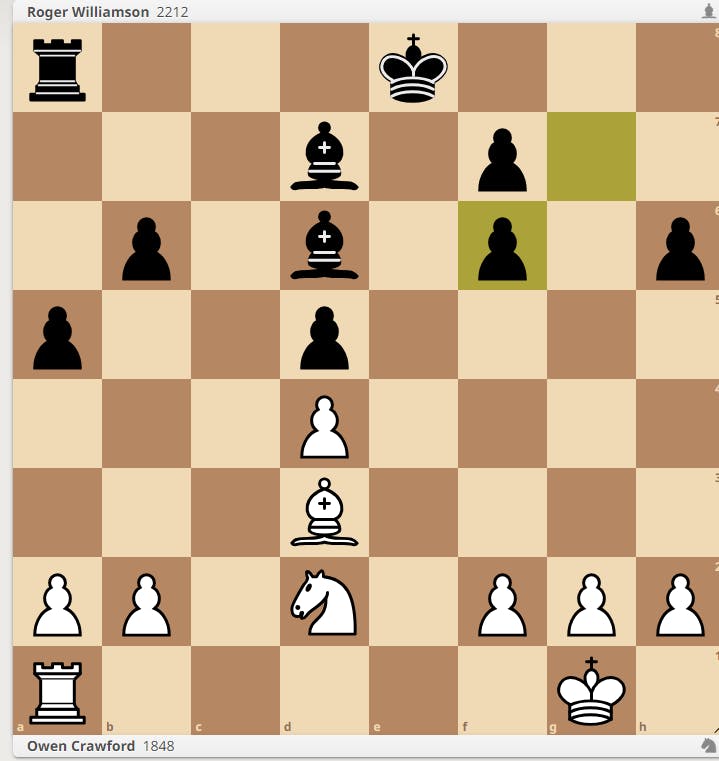

It appears I did not learn my lesson, as less than a month later, in the John Ripley Cup final, I found myself in this position:

Black to play.

And rather than the obvious and thematic 18... Ne4!, inviting white to play Bxe4 and surrender all the light squares, I decided to play the extravagant 18... a5?!. To which white responded 19. Nd2 ,and I answered 19... h6?, needlessly permitting white to damage my kingside pawn structure with 20. Bxf6 gxf6.

Why?

The answer is banal. Because in one of my favourite Grandmaster games, Bologan - Zvjaginsev, 2011, (analysed elsewhere in this blog in the article 'Planning & Prevention') black demonstrated that a bishop unopposed by its counterpart can be enough to offset a missing pawn. I may not be missing a pawn in the position above, but after 21. Nf1!, heading to e3 to attack d5, I'm far from comfortable, tied down as I am to both protecting d5 and watching the squares on the kingside weakened by my allowing my structure to be shattered - another two-result position where I can only draw or lose.

I managed to save both these games, but not without a little ingenuity and more than a little luck. Does my having saved them prove Kasparov's point? Yes. Does it mean I am liable to make the same practical mistake again? Also yes. In truth, losing either game might have done me a favour. It would have put greater onus on me not to repeat the mistake. But, alas, the mouse is a creature of habit. And not having lost, I may actually be happier, more at home in my maze than out of it.

You may be wondering why I chose the mouse as a metaphor, considering the words 'laboratory' and 'rat' go more readily together. It's not because 'rat' has more negative connotations than 'mouse'. It's rather that a rat is more concerned with escaping and breaking the pattern, breaking the circuit.

Analyse your games. Identify your favourite mistakes. Become more rat than mouse.