'What openings should I play in order to improve?' Is a question frequently asked of this chess coach by a casual student. More often than not, my answer is 'whichever openings you enjoy playing'. Unless as a student you're prepared to wholly submit yourself to your coach's suggestions (and few are!), your openings are your own business. But an explanation as to why specific openings are and have been more or less popular at the higher levels, and are thus considered superior to others, and why it might matter, is valuable knowledge.

Superior openings offer more wriggle room: Bottlenecks Vs. Departure Points

For purposes of argument, let's assume a hierarchy in which openings are divided into three tiers according to their historic popularity in master chess: 'top', 'middle', & 'bottom'. Then let's focus exclusively on defences to 1. e4. In the top tier we'll place 1... e5, the French, the Sicilian, and the Caro-Kann. In the middle tier we'll put the Scandinavian, Alekhine's defence, the Pirc/Modern, Owen's defence, Nimzowitsch's defence, and others. And in the bottom tier, we'll place the variety of senseless first moves like 1... a5 and the horde of wacky gambits that, if opponents were properly prepared with white (a huge 'if'), or capable of refuting them over the board (an even bigger if), would leave black at a more than slight disadvantage.

Now let's take a top tier defence to e4 and compare it with one from the middle. In this instance, the French defence vs. Alekhine's defence.

In the French, the most forcing option for white, the Advance variation, has at least three answers that offer black at the very least a manageable disadvantage: 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. e5 c5 4. c3 Nc6 5. Nf3 can (currently) be combatively met by any of 5... Bd7, 5... Qb6, or 5... Nh6. Three points of departure that combined could fill a book with viable ideas for black.

In Alekhine's defence, on the other hand, we encounter a problem in its most forcing line: 1. e4 Nf6 2. e5 Nd5 3. d4 d6 4. c4 Nb6 5. f4, the Four Pawns Attack. As Alexei Kornev observes in his 2019 book on Alekhine's, only one black answer to the Four Pawns has so far 'withstood the test of time': 5... de 6. fe Nc6 7. Be3 Bf5 8. Nc3 e6 9. Nf3 Be7 (For anyone looking to quibble with this assessment, the analysis of the Four Pawns presented in Gawain Jones' 2021 Coffeehouse Repertoire: Volume I is what they must overturn.) This represents a bottleneck, a narrowing of viable options. Even if, as Kornev says, black should be 'ok' in this line providing he memorise the narrow path out of the woods, it would only take a new theoretical wrinkle to see this bottleneck become a stopper, and the previously secure path to an uneasy equality now lead to disaster.

Which hasn't prevented Magnus Carlsen from winning with Alekhine's defence. However, when Carlsen has played it, he's purposefully avoided playing black's best line versus the Four Pawns. Presumably on the grounds he either believed that's where his opponents would have extensively prepared, or he didn't believe in black's position (or perhaps a combination of both). Black has problems to solve in all openings. The best players find ways to solve them regardless - even if the solution is temporary and sometimes takes the form of gamble.

Similar but Inferior

The ongoing revolution in chess analysis software has led to a reevaluation of what constitutes a playable opening. For instance, it's thanks to AlphaZero that 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 d5 3. cd Qxd5 has been upgraded from its place in the bottom tier of defences to 1. d4 to a place somewhere in the middle, becoming briefly fashionable at a very high level. The likes of Shakhriyar Mamedyarov have, presumably with the aid of engine preparation, ventured lines as unlikely at super GM level as 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nf6 3. Nxe5 Nxe4 as black, knowing that a) their opponents are theoretically and psychologically insufficiently prepared to face it, and b) extensive testing with the engine has revealed nuances hidden from previous analysts.

Nevertheless, despite the arrangement of our hierarchy of openings proving not to be so prohibitive as may have been believed in the Kasparov era, when human intuition reigned supreme, there are still good reasons to believe in it. Take Owen's defence, 1. e4 b6. No less a player than Christian Bauer (a sometime 2600) has written a book advocating for it. Like Alekhine's (not coincidentally, also the subject of a book by Bauer), it too features early bottlenecks in its theory that might restrict its user's ability to wriggle. But why is this so? Owen's frequently results in French & Sicilian-type middlegames. The queenside fianchetto, after all, can be integral to both the Sicilian and the French defences. Well, the devil is in the small differences.

Take a look at the following diagrammed positions. Should an Owen's defence come to resemble a French, after an eventual ...e6 & ...d5 by black, then the bishop would be prematurely positioned at b7. From its original square on c8 the bishop might more easily effect a ...f6 pawn break, standard in the French, by protecting the resulting backward e6 pawn from attack.

French (left) vs Owens (right)

Should black instead play ...c5 and turn the game into a kind of Sicilian, then he would typically rather have his pawns on a6 & b5 rather than a7 & b6 so as to realise an eventual minority attack.

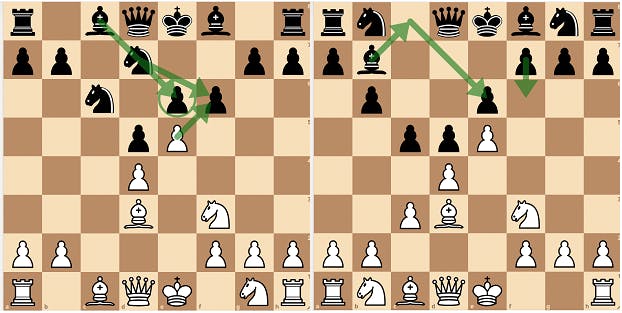

Sicilian (left) vs Owens (right)

So why, other than reasons of taste, temperament, and game psychology would players at the higher levels regularly opt for Owen's defence over either the French or the Sicilian?

It may come to pass someday that the volume of theory for Owen's defence expands to rival or even surpass that of top tier defence like the French. Increased praxis may see today's bottlenecks become tomorrow's departure points. Stranger things have happened. Yet it remains unlikely, because not only is the past is our best guide to the future, there are conceptual reasons why certain openings are considered 'best by test'.