There's a general consensus that GM Hikaru Nakamura is in the best form of his life. Given that he's won several major tournaments, qualified for the Candidates and then came within half a point of reaching the final itself, it's hard to disagree. He's also repeated the mantra over the last couple of years that he no longer considers himself a chess player. He's a livestreamer. If the above achievements aren't too shabby for what he claims is essentially a side-hustle, it's all down to one thing - the lack of pressure. After qualifying for the Candidates, he repeated it, 'I won't be under as much pressure as the other players.'

At first I thought this probably disingenuous - can you really be a part-time member of the world's elite? Is that a not-so-subtle way of declaring your genius? Or was it a kind of defence mechanism, a means of lowering expectations? As these high standards continued though, I began to think it really might be true; the lack of pressure under which he's playing is leading to exceptional performances.

At a less rarefied level, and under different types of pressures (which come in many flavours) then wouldn't reducing them possibly improve all of our chess too? Although none of us (I assume) have lucrative livestreams, we are not primarily chess players either, so why are we lowering the quality of our games by investing so much into them?

In this case we are not talking about the pressures of playing for hundreds of thousands of dollars of prize money or clawing to keep yourself in the top 10 but the pressures that are met with all the time, at any level, at the chessboard itself. With this in mind I thought I'd give some examples from my own praxis. This is because it's impossible for me to comment on anybody else's thought processes other than my own. Plus some are quite funny.

There's no actual chess instruction in this; but there might - might - be the odd thing you can pick up about other aspects of the game. Where team names are given above the diagrams, they are the opponents in the Merseyside League of my then team, Aigburth.

YOU HAVE TO WIN...

... said our Board Two, a very strong player. I'd just reached the time control (back then, 35 moves in I hour 15 minutes, with 15 minutes for all the remaining moves - no increment) after a scramble in which I'd raced through my last 6 moves in two and a half minutes and managed to hit move 36. I'd just got up to check on the other games when, before I'd taken half a dozen steps, I was pulled to one side and issued this stern instruction. Rather unsettled by the ultimatum I cut short my walk and returned to the board to find that my opponent had already played the forced 37. bxa3

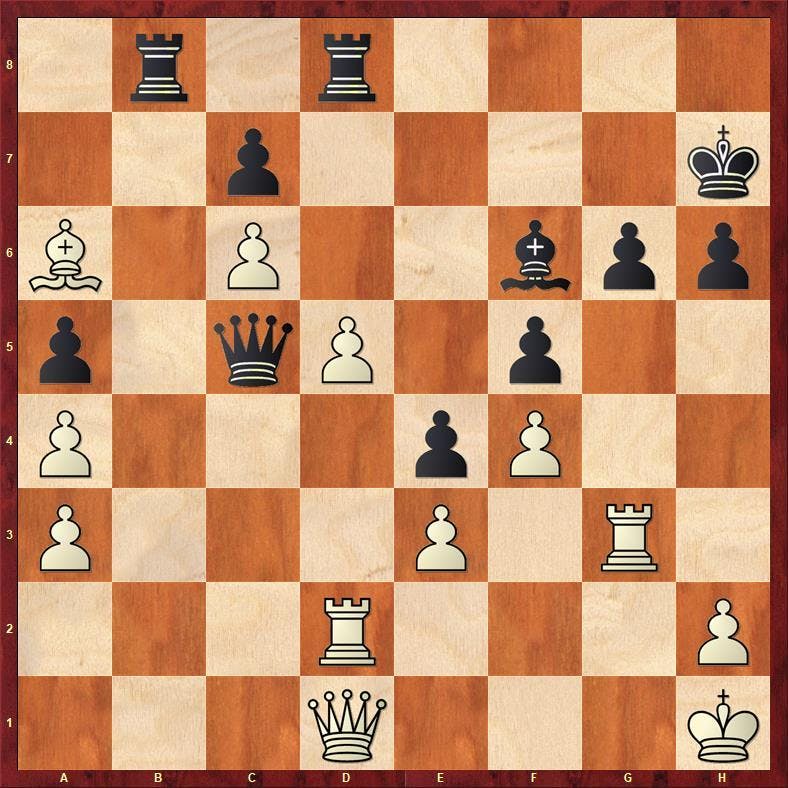

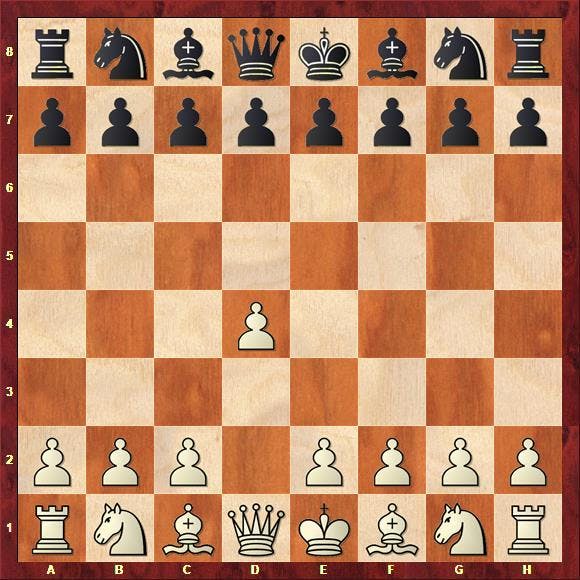

McCarthy - Frith

Atticus II (h), 2009

Black to play and… win?

What to do? It's the type of typically confused position that can arise from a Leningrad Dutch. Perhaps I have some kind of edge - but I have to win. How? I sat cudgelling and puzzling my brain, using up several more precious minutes. 37... Qxa3 allows a dangerous-looking 38. d6; doubling rooks on the d-file might just be met with a Rc2; is the White bishop going to go to b5 and block my open file? Too many questions with time ebbing away. Eventually I decided that my only feasible winning plan would be to apply pressure to the e3 pawn, perhaps double rooks on the b-file, infiltrate and... something. So I tried 37...Rb3??

My opponent looked at the move for a bit, suspiciously. Then he looked at me with a puzzled frown. Then reached out and played 38. Qxb3

I looked at the move for a bit, suspiciously, then looked at him with a puzzled frown, then reached out my hand.

I was still confused the next day. It's without doubt the worst move I've ever played on a chessboard (if not even the worst blunder - see later). It deserves four question marks. But how did it happen???? A queen is not hidden behind a rook. It's well-known that many blunders happen on the last move of a time control. Strangely, many also happen on the move after the time control, when a player fails to adjust and reset after what has often been a frantic last few minutes. Was it because my walk had been curtailed and I hadn't time to calm myself? Maybe?. I came to the conclusion though that the ultimate culprit was the pressure of knowing that I had to win. Instead of playing the position on its merits, finding ways to improve the pieces or force concessions, I'd desperately tried to find a way to bludgeon my way to victory and in the process completely scrambled my brain.

There aren't many lessons to be drawn from this - it's mainly here as an extreme example of how pressure can affect our chess. If it does teach anything, it's 'don't tell your team-mates that they have to win'. At least not while they're in the middle of a game. Give them the current match score and raise an eyebrow, maybe - no more. In a tournament it's often obvious beforehand - you might 'have to win' the last game of a tournament to get first place, for example. Or in preparing for a match, your captain may have identified your board as a very good candidate for an important victory and instructed you as such. In these cases though, you enter the game with a clear idea of what's required. To suddenly switch to 'I have to win' midway through a fairly equal struggle though, is a pretty good way of telling your mind that 'you're going to find a way to lose.'

THE PRESSURE OF WINNING A WON GAME

This is well-known. There are numerous variations on the quote, 'There is nothing so difficult as winning a won game,' ascribed to various, usually German, players of the early 20th century. I don't like the phraseology though and prefer to use the word 'won' for a game that is indisputably, well... won. I'd rather describe the phenomenon as, 'the difficulty in ultimately converting an advantageous position into victory.' Which is why you won't find my name in any book of aphorisms.

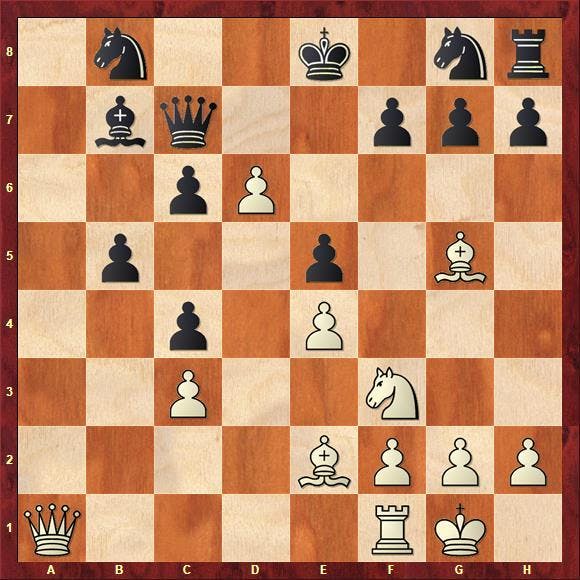

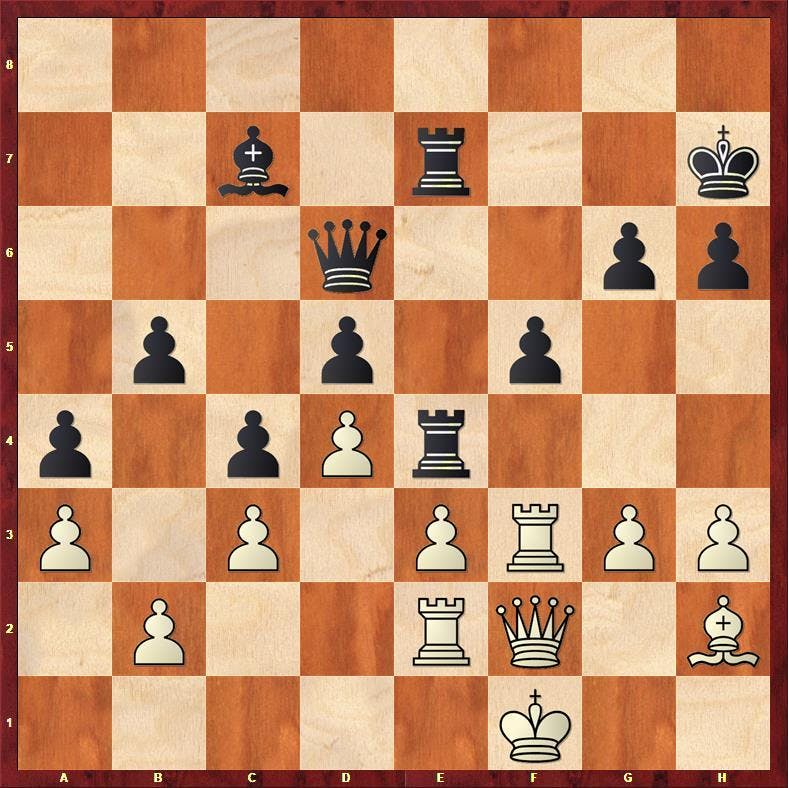

In my own practice, the following game is the worst experience/best example of this in action. It is the 1st Round of the Heywood Major and I have been given White against David Bryant. David is a stronger player than I and was probably one of the favourites for the tournament. However, in one of those strokes of luck that happen all too rarely in chess, I'd been able to use a transpositional trick in the opening that I'd been looking at just the week before; this somewhat confused him and after my last move 15. d6! {diagram} Black is already in huge trouble right out of the opening. In fact Stockfish gives this as +4.00 or thereabouts. I didn't know that at the time, obviously, but I knew I was almost certainly 'winning'.

FRITH - BRYANT

Heywood Major, 2009

Black to play, White to win the won game

There followed 15... Qc8 (15...Qxd6? 16. Rd1 +-)16. Nxe5 Nf6 17. Bxf6 gxf6 18. Bg4 (inaccurate but White is still hugely better) ...Qd8 19. e7+ Kf8 20. Qa7 fxe5 21. Qxb7. My moves haven't been very incisive but they're still enough for a sizeable advantage.

I should have heeded the warning signs in my preceding play though. Instead of really trying to find the most clinical moves I'd been playing 'ok' ones in the belief that my position would eventually win itself. Although it's only move 21, I have only 25 minutes left for the next 19 moves. So I've certainly been thinking; but about what? Without any clear plan of what I'm trying to achieve. I clearly remember the slowly mounting sense of frustration that followed.

21... Kg7 22. Rd1 Rg8 23. Bf5 Kh8 24.Qa7 Qg5 25. g3 Rd8 26. Qc5 Qf6 27. Qe3 Kg7

White to play and win the won game with a knockout blow

White to play and win the won game with a knockout blow

Here any engine points out that 28. Rd6! Followed by 29. Qg4+ and 30. Qxd8 wins on the spot. Did I search for the killer move that must be in such position? No. I no longer believe in anything. I played the largely meaningless 28. Qf3, painfully aware that I still had no idea what I was aiming for; it's not that Black is constructing an ingenious defence - there isn't one - the game is going to be decided by the fact that I'm now annoyed with myself, bemused that the game's not already over and increasingly worried about my time. 28... h6 29. h4 Kf8 30. Rd2? - and with that an entire game's worth of advantage is thrown away - 30... Ke7? David was probably also in time trouble. The pin on my bishop means my pride and joy on d7 can simply be taken. But the position is now equal in any case. Unless White does something stupid... 31. Qg4 Na6 32. Qd1 Nc5 33. Bh3? Nxe4 34. Re2?? Nxc3 0-1

Finally the winning game is won – for Black

I absolutely could not believe this had happened. How on earth do you even lose a 'won' game in - three moves? I was so furious and full of self-hatred after this experience that I went wild in my next game and lost that too. Luckily I did the professional thing, rallied myself for the next day, bounced back and ended the tournament with a respectable score. No, of course I didn't. I lost both of the following day's games in abject fashion as well. A competition that had begun with such promise ended with me scoring 0.5/5.

The extra half point was because I took a first round bye.

My advice would be to banish the word 'winning' from your vocabulary altogether. Naturally as chess players we all use it in analysis, it's a useful shorthand, 'Well, this must just be winning,' etc. But while actually playing your games, forget it exists. Maybe forget even the word 'better' exists. Look at the position and think, 'This is quite a pleasant position, so what now?' If you would have formerly described it as 'winning' then (so long as your judgement is correct) there must be some aspect(s) of it that you define as very good. Do you have an attack? Then try to find a way for it become overwhelming. A positional advantage? How can you increase it or exchange it for other gains? A material advantage? Do you swap off into an endgame? Attack a weak point? In short, you think just like you would normally - as if you weren't so-called 'winning'. My example shows that if you think a game will win itself, it won't, if you think you can play second-rate moves and still win, you can't, and if you think there's no danger of even losing your 'won' game - you're wrong.

THE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING

I started playing chess competitively at a very late age. As such, my biggest fear was that all the gnarled pros I met in the league would have decades of experience in their pet openings behind them - how could I compete? When I was beginning chess one of the few books I had access to was from the local library, 'Nigel Short On Chess'. Short wrote that a good opening for beginners was the Torre Attack; simple to play and you can't get into too much trouble. Which seemed ideal. So when I first started playing online, as White I played exclusively some form of 1. d4 2. Nf3 3.Bg5 4.e3 etc. and it served me well enough. Therefore when I began playing OTB league chess I did exactly the same. Besides I knew nothing else. It took me about a decade before I realised that I needn't have been so worried; at the level I played at hardly anybody knew hardly anything about hardly anything. I'd been playing a few months when my team-mate Brendan, who'd introduced me to the club, said he was going to play in a tournament - why didn't I come along and play in the Minor section? I agreed - but not without trepidation...

If the Merseyside League was full of opening experts, how much more intensive would the knowledge be of players who were in a serious tournament? Where there were plaudits, and more importantly, cash prizes at stake? My Torre is not going to hack that. Besides I'd learned that serious players did preparation for big events - so I should too. And what if people had been closely following my career and realised that I only played the Torre, then came armed to the teeth against it? I needed something else. Then a few days before the tournament it came to me - the English!

Granted, I knew absolutely nothing - nothing - about the English. My 'theory' ran to 1. c4 2. g3 3. Bg2 End of line. My idea was that nobody played the English, I'd have no idea what I was doing but neither would they, we'd get to move 4 on a level playing field and then my chess genius would take over. As mad as this sounds - and it is - it actually lessened my worry about the tournament. I had my secret weapon. I was content. I was confident.

Day of the tourney I entered a maelstrom. I didn't know where to pay. People crowded around the desk. I had no idea what I was doing, Brendan telling me I had to go and look on a board to try and see who I was playing, finally getting through the scrum on that, realising I was looking at the wrong board, finding the Minor one, finding my number - White! English here we come! - failing to find my numbered actual chess board in the hall amongst seemingly hundreds, so, milling around... I eventually located it amongst the sections, sat down, an arbiter far off said - something - and everybody started. And I had no opponent.

So I sat there. How do you play without an opponent? I honestly didn't even know if I was allowed to get up from the board to go and ask. After a few minutes, mortified that this must already be really bad etiquette, I nudged the bloke next to me, already a dozen moves into what was probably a Spanish, and said, 'I've got no opponent. What do I do?'

'Press the clock,' he said.

So I pressed the clock.

After a few more minutes he glanced over again and added, 'You have to make a move though.'

Whaaatt?! I now realised that I was cheating. I'm White. I should have made a move and then pressed the clock. I've been stealing his time. Quickly I threw a pawn forward, pressed the clock back to my side, stared intently at the analogue display to try and balance out how much time I'd robbed from my opponent and even it up, then finally, satisfied, re-pressed the clock to his side. I sat back, moral duty done; then looked at the board. In horror.

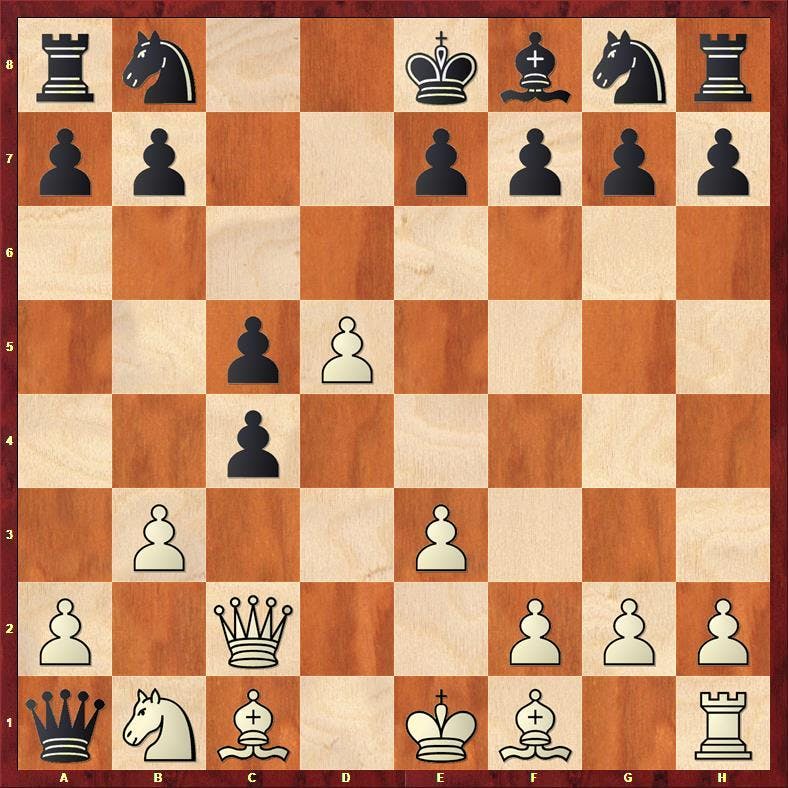

Frith - Dawson

Heywood Minor, 2006

1.d4?? A wreck of a position

Oh, no, what had I done?? Where was my secret weapon, my English? I sat back in my now seemingly very loud chair in utter disbelief at what had happened. In the panic, muscle memory, had taken over and my hand had simply picked up the pawn it had always previously picked up - the d-pawn - and moved it. I stared at my wreck of a position in misery.

This may seem insane to you. It was the opening I usually played, so what's the problem? The problem is I wanted to play 1. c4. The problem is, I'd spent half an hour bumbling around the playing hall like an idiot, then committed a rank breach of chess etiquette, then cheated on the clock, and then somehow, in my very first tournament, with my very first move, managed to blunder. As White.

Shortly afterwards my adversary turned up and replied 1...Nf6 I half-heartedly did some Nf3 and Bg5 stuff and lost as I'd convinced myself I would ever since I saw the first position.

This is a lesson in basics. The stress of unfamiliarity. All the pressure I felt that morning was down to not having a clue what I was doing and could have all been avoided if I had. So deal with the basics. Do you know where the venue is? When the round starts? The competition rules? Do you have a pen? A backup pencil? Glasses if you need them? If you're a captain do you know those competition rules? Have your players' phone numbers? Opposition captain's? It's not facile. Getting all this stuff right means you can concentrate on what's important, i.e. the actual chess. And it's not confined to beginners. There are numerous Grandmaster examples of those who didn't know what time a game started, who fell foul of the tournament dress code. Do you even know the chess rules properly? There are Super-GMs who have admitted to not knowing the castling rules in certain Chess960 positions. Wesley So was somehow unaware that you aren't allowed to write motivational messages on your scoresheet. Do you know how to queen a pawn properly? The time to realise you don't know the procedure for trying to claim a draw by threefold repetition is not when you're just about to try and claim a draw by threefold repetition.

THE TIME PRESSURE OF ANTICIPATED TIME PRESSURE

Time trouble is the most well-known of the stressful situations we may encounter and undoubtedly the cause of more anguish and blunders than any other. A very few players seem to actively enjoy it. While we can read about Reshevsky (Samuel Reshevsky perpetually left himself a couple of minutes to play twenty or thirty moves before - triumphantly - reaching a time control - Roger) and marvel at Grischuk's ability to play world-class moves with just seconds on his clock, there's no doubt these foibles cost both great players points and half points during the course of their careers. Me, I can't stand it and am absolutely awful if I end up in it. To this end, I figure it's a good trade-off if I make some sub-optimal moves relatively quickly during a game as opposed to making truly terrible ones when my clock is ticking down. Time trouble has been covered so extensively that there's no need to deal with it any further. But here's a curiosity - how about time pressure before the time pressure?

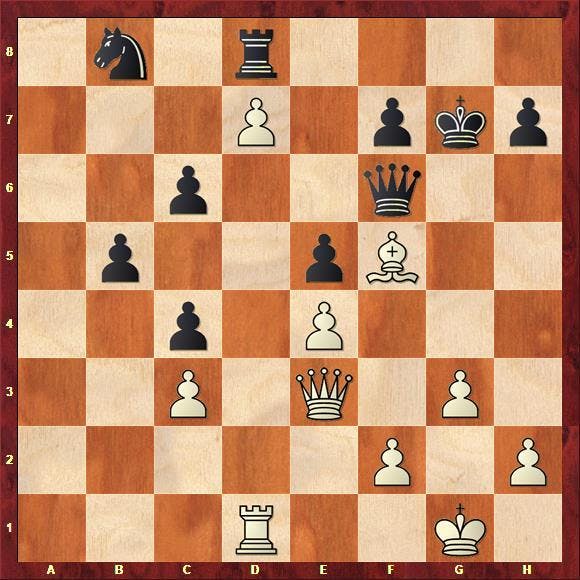

FRITH - TSABOSHVILI

Cork Masters, 2008

Black is better of course.

But he's been better for the last two hours and not done a damned thing about it. The last 35 moves or so have seen an endless shuffling of bishops, minor adjustments of rooks, a back and forth of queens - with roughly the same position as on the board and absolutely no progress made. This wasn't strategic manoeuvring, he wasn't even trying to win so I'd offered a draw a few moves previously - which he'd refused. I was annoyed. Then his plan struck me. While I'd been taking time looking for ways out of the impasse and trying to find ideas, he'd just been making random moves - and was now 20 minutes ahead on the clock. He was either just going to make me run out of time (no increment) or wait until I had a minute left before doing anything - in which case I'd play terribly anyway. So in the above diagram, out of desperation, with 20 minutes still on my clock, I played 55. g4? - a time trouble move before I'm even in time trouble - fully aware that breaking open the position was daft and that I was losing a pawn after 55...Qxh2 56. Qxh2 Bxh2 57. Rxh2 Rxe3 (57...fxg4 first may have been more accurate) and in all probability the game. But what else? I have to do something. I lost in due course (0-1, 78)

I managed to shake his hand afterwards but it was through gritted knuckles. I felt cheated, that this was a really low way to win a game of chess. In later years I realised that was stupid. He was entitled to play however he wanted. The fault was mine for allowing myself to get so behind on the clock as to put him in that position. And for not saying, 'Ok then, buddy' and moving the king between g2 and f1 or something on every move, taking a second each time. With the piece configuration I'd never have been able to force a threefold repetition but at the very least, to avoid the 50 move rule, at some stage he'd have had to move a pawn. Then at least he'd be the one having to change the dynamic. Even if in a minor way. And at least there'd be progress.

There's not much chess advice to give if you're ever in the same position, just do the above. And if you hate time trouble be aware that its spectre can reach back even into the middlegame. With increments you won't get flagged at least, so don't panic. That can come later.

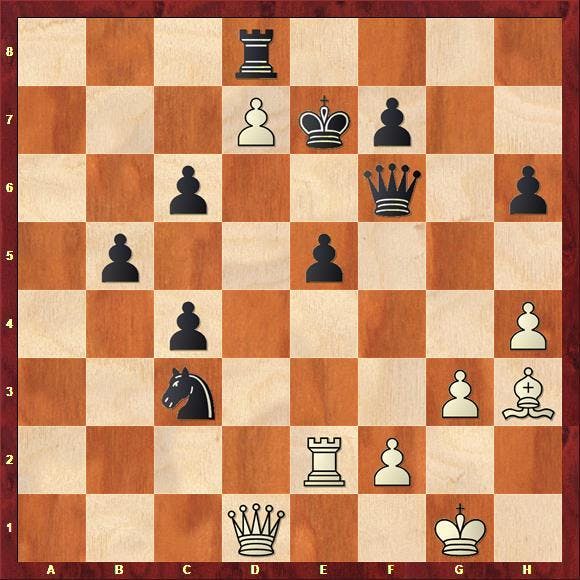

THE NON-PRESSURE OF THE LOST GAME

FRITH - HOSSEIN, E

Atticus I (a) 2009

White to play and enjoy himself

Black has just played 9... Qxa1 and I've just blundered my second rook in a year. I'm giving rook odds in the opening and my name's not Morphy. I'm lost. Beginners playing each other should probably never resign as any blunder you may make could easily be reciprocated by one from your opponent. Otherwise, everyone will have their own demarcation lines, usually corresponding to playing strength, as regards the time to resign. To continue for the hell of it when it's clearly hopeless is just bad sportsmanship. Here, there are many pieces left on the board (minus a rook) and he has no development; it's cold outside; and I didn't fancy going to catch my captain's eye to tell him I'd lost in under 10 moves. Ironically, it turns out that he was a very strong player who for some reason was playing down the order. If I'd known that I would have resigned; but I thought he was just a 'normal' Board 5, like myself. So I kept a straight face, hoped my opponent would think it was part of some deep computer preparation, decided I'd play on at least for a little bit and quickly replied 10. Bxc4. After happily throwing my pieces around, here is the position after 26... Qb6

Not too bad y’know

If I'd now played 27. Qf5 (I didn't; in severe time trouble I played the idiotic on many levels 27. Kxg2? (What?) and resigned 4 moves later) then yes, I'm still 'losing' but I'm no longer 'lost'. In fact Black needs to keep his nerve and a clear head or he may even begin facing some serious problems himself with those advanced pawns. The point is though, that since losing the rook I'd been able to play happily, utterly without stress - and really enjoyed myself!

If you're lost - provided it's not obviously resignable and you're not just being a tosser - you have the freedom to do whatever you feel like. Mount a wild attack, sac more pieces, go out in a blaze of glory. If you're 'worse' you have to struggle as hard as you can to try and find equality. If you're 'losing' you have to search for every resource there is and try and set your opponent as many problems as you can. If you're 'lost' - well, knock yourself out. For a few moves at least. The worst has already happened, the board's your plaything - and rarely for chess, you'll be able to do it all totally pressure-free.

THE NON-PRESSURE OF THE WON GAME

After all the above and as I've already been used as an example of how not to play elsewhere on the site (in one of Roger's excellent articles), so that this article doesn't begin to look like an exercise in mediaeval self-flagellation and that I've spent my whole life making ridiculous blunders and hanging rooks, I thought I'd end on a more positive note. This time I hang a queen. To win.

Aigburth were trying to win the league, which hadn't been won by them in a while. With just three fixtures remaining after this one, every point was vital. With half the games over in this match things were level and the atmosphere tense. I'd had an advantage, then my opponent had, and now we'd reached the position below were almost anything can happen.

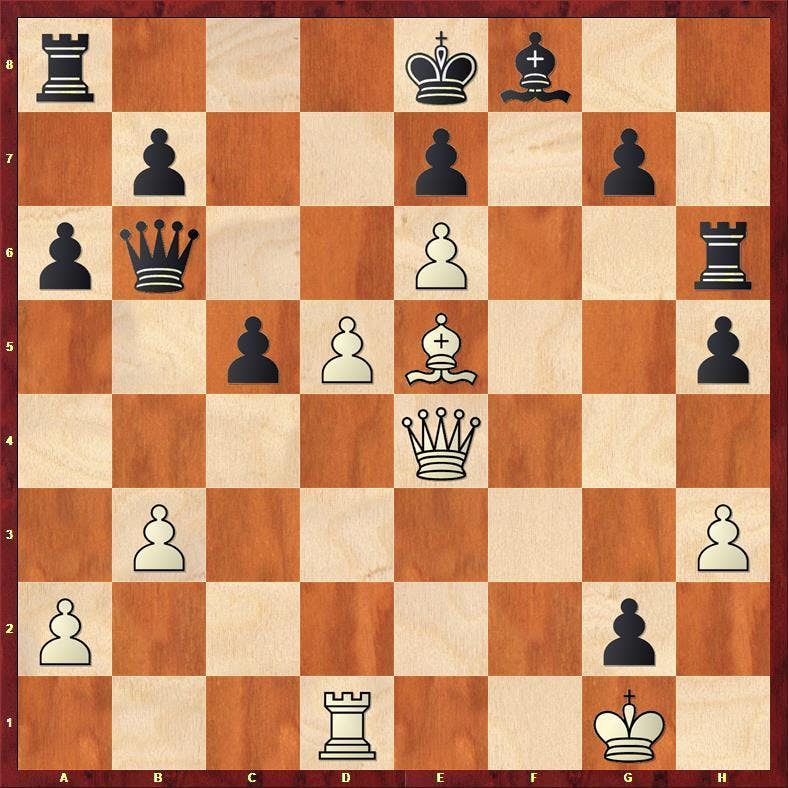

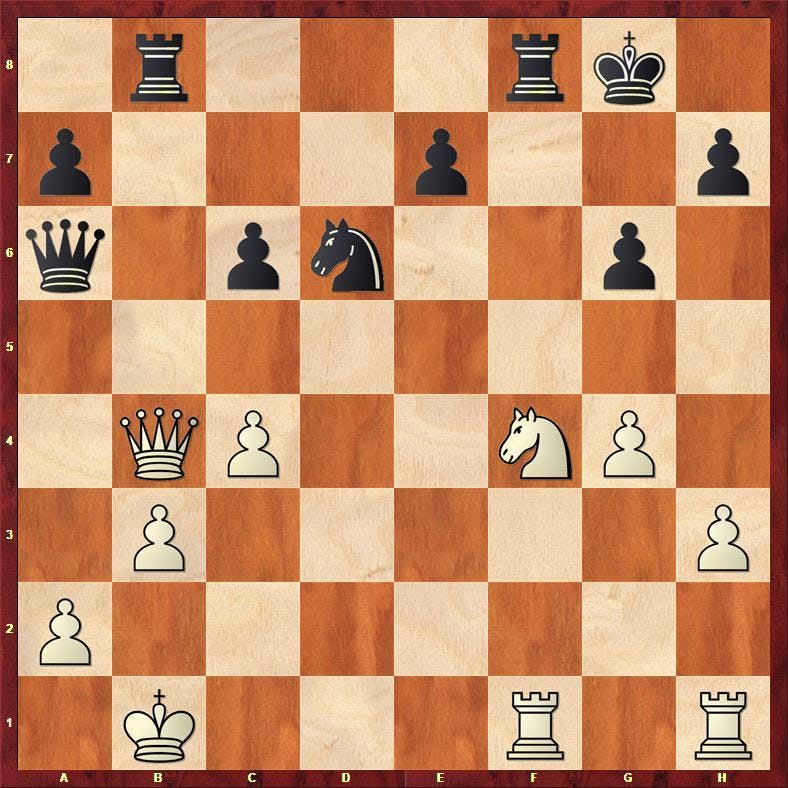

FRITH - TAYLOR

Wallasey (a) 2010

White to play and be carried out of the club shoulder high by cheering team-mates

Mr Taylor has just played 29... Rab8?! It seems almost harsh to give this move a 'dubious' sign. It looks the most natural move on the board, one many of us might have tried. It develops the rook to a half-open file via a big hit on the queen, and introduces latent threats of ... Nxc4 or even a (much) later rook sac on b3. What's not to like? The problem is there's an immediate if visually surprising refutation with 30. Ne6!

Play continued 30... Rxf1+? Perhaps the move was also psychologically shocking. The immediate 30... Qc8 had to be played though after 31. Qe1, White keeps an advantage. After 31. Rxf1 In a Christiesque plot twist, it turns out that despite leaving the queen en prise while simultaneously allowing a heavy piece capture with check, it's not the White queen that will end up hanging - it's the Black rook. 31...Qc8 32. Qe1 Nf7 32. Qe2 and White was much better (1-0, 39)

After it was over, a team-mate whose game had already finished and had been watching, whispered to me, 'I don't know how you played that knight move! I wouldn't have had the nerve.'

'Well it was won!' I replied.

And it's true. I'd love to say that the move was bold or daring but sadly it wasn't. It took a small leap of imagination to see it existed but after that it was simply a case of, 'Well the queen can't be taken or it's mate. If the rook is captured first it still can't be taken - it's the same mate.' And that's it. A simple two-move calculation that we can all do. If it's won, it's won. No pressure whatsoever.

That's the beauty of being 'won' - there's no pressure. If you have a theoretically won king and pawn endgame and you know how to convert it (and have the time) - it's won. If there's a mate in two and you see it - it's won. There's not a single thing your opponent can do about it. They can crunch crisps, fidget in their chairs, kick your shins, it doesn't matter - it's won. You can be playing clubmate, Carlsen or Stockfish, it makes no difference - it's won.

THE PRESSURE OF TRYING TO SUMMARISE AN ARTICLE ABOUT PRESSURE

After all of which you may be thinking, 'Well so what?' If we've established that the only time that pressure doesn't exist is when you're totally won or totally lost, what does that mean for the remaining 98% of the game when those extreme conditions don't exist? Well, the last two examples were a piece of misdirection; because it doesn't exist during the rest of the game either. Pressure is not a physical entity hiding in the board and the pieces, waiting to jump out at you. In all of the examples given above it was entirely self-inflicted. Some had practical causes - not knowing what I was doing, not knowing the rules, not dealing with the clock. Some had mental causes - prematurely relaxing, getting frustrated, being unable to deal with an advantage. But none had to happen. The practical ones can be eliminated by practical means, the mental ones eliminated mentally. If you don't deal with them then, without getting too Alan Watts about it, the entirety of pressure you feel during a chess game, is the pressure that you - yes you - have chosen to put upon yourself. If Nakamura can play free of his pressure, then we can play free all our various pressures too.

Ultimately when you sit in front of a chess board you have only one task. To look at the situation in front of you; and given your current knowledge, experience, ability and emotional state, and within whatever time is remaining, make the best decision that you possibly can. And that's something we all do naturally every moment of every day. It's otherwise known as living.