The Caro-Kann is currently immensely popular. This is no doubt less to do with its endorsement at the highest level by Anand, Carlsen et al and more to do with how and where new chess players (those who came to the game during the pandemic) get their information. The most popular chess YouTube streamers, Levy Rozman and Eric Rosen, advocate the Caro for black. And they do so because black immediately puts his 'problem' c8 bishop on f5, outside of the pawn chain. But with that freedom for the bishop comes great (in the chess sense) responsibilities. The direct confrontation Caro produces, with its frequently immediate exchanges and open board, means that games often become a matter of technique. What I mean by technique is that winning with the Caro seldom involves huge attacking gestures by black. Rather, black must convert imbalances in otherwise equal positions.

One such imbalance is the knight vs. bishop middlegame/endgame that can occur in the Classical lines. In such positions, the black knight must outshine the white bishop. Just not as a solo artist. The knight leads from the front, like the first violin in an orchestra, but it cannot play the symphony on its own. Like in an orchestra, it must be in harmony with the pawns and the heavy pieces as it follows the hand of the conductor, and by virtue of having more notes to play shows its fellow pieces where to come in.

What follows is not yet another exposition of the theme of 'good knight vs. bad bishop'. The white bishops in the following games are neither 'bad' in the sense they on the same colour complex as their central pawns, nor are they bad in the literal sense of being wholly impotent. They sit and point and exert power. But that's all. The black knights, on the other hand, and by virtue of where they're going next, tell the other black pieces what to do and how to win or save the game.

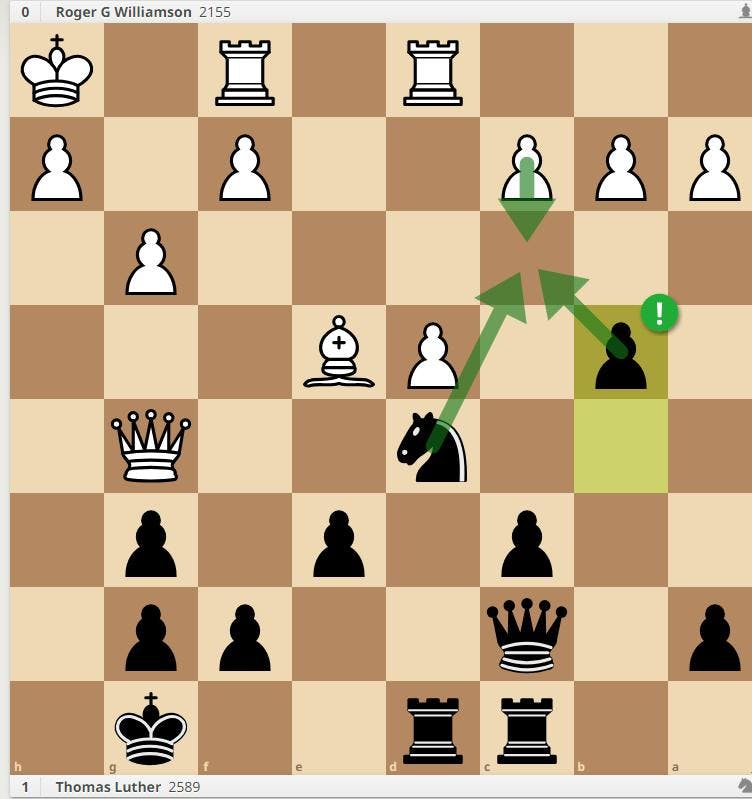

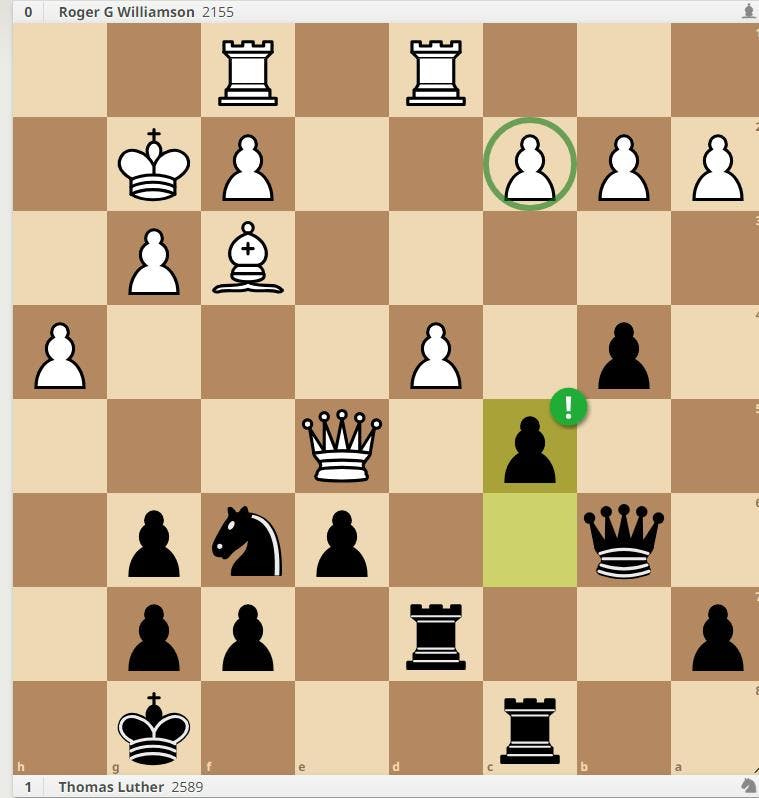

Roger Williamson (2155) - Thomas Luther (2589) Liverpool, 2006

When you have a middlegame position as I did in the following game, the feeling is very much one of fatalism as you dance to your opponent's tune. Regardless that the engine will insist the middlegame that arises from this Classical sideline is equal, your attention is drawn to the reality that black's centralized knight gives him options, whereas the opposing bishop restricts white merely to waiting for something to happen.

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Bf5 5. Ng3 Bg6 6. Bc4

A thematically similar though distinct sideline. The combination of 6.h4/Nf3 7.Nf3/h4 is the Classical mainline.

6... e6 7. N1e2 Bd6 8. Nf4 Nf6 9. O-O Qc7 10. Qf3 O-O 11. Nxg6

White 'wins' the bishop pair. But to meaningful purpose.

hxg6 12. Kh1 Nbd7 13. Ne4 Nxe4

More exchanges bring black closer to the desired Knight vs. Bishop position.

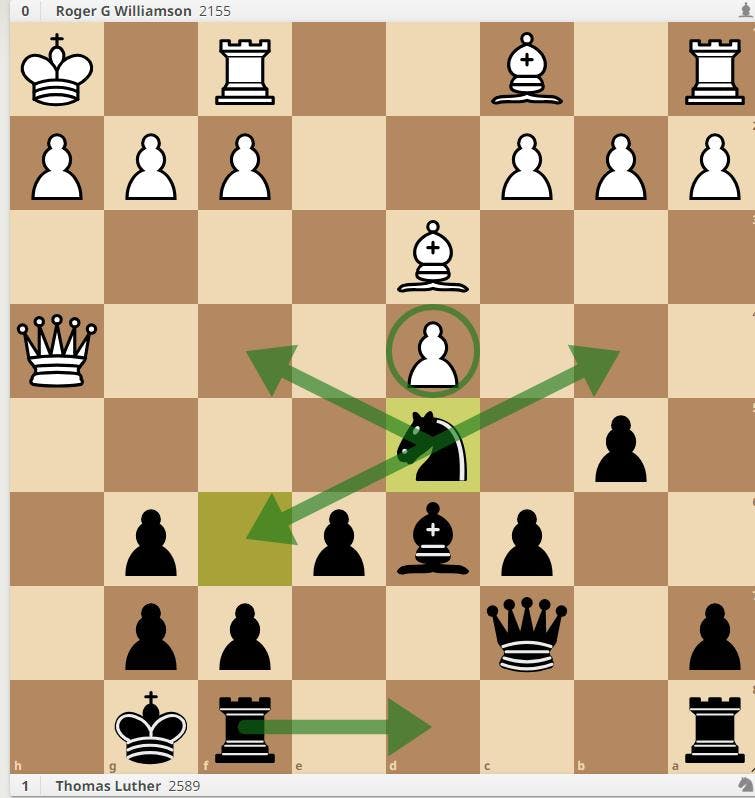

14. Qxe4 Nf6 15. Qh4 b5 16. Bd3 Nd5

It's quite usual for players at first glance to prefer the bishop pair here. But that black knight on d5, in conjunction with the black dark square bishop, prevents the white dark square bishop from making any real contribution to the game. It also suggests to black that the d-pawn the knight blockades should be pressured by a rook on d8.

17. Bd2 Bf4

Forcing the exchange and negating the bishop pair. Here, instead of the incrementally suffocating positional grind, black also has the option of transforming his advantage in the center to play on both wings. After 17... f5! 18. f4 Kf7! 19. Qf2 a5 20. h3 a4 black's position, with the half-open f-file and the advanced queenside pawns, is very aesthetically pleasing. And in the middle of it all is the d5 knight:

Black picks up the pace.

18. Bxf4 Nxf4

Here the engine will express a slight preference for the knight over the bishop. However, the knight is much the stronger piece. The most the bishop can do is sit on the h1-a8 diagonal and look pretty. The knight has the d5, f6, and d7 squares available to tour.

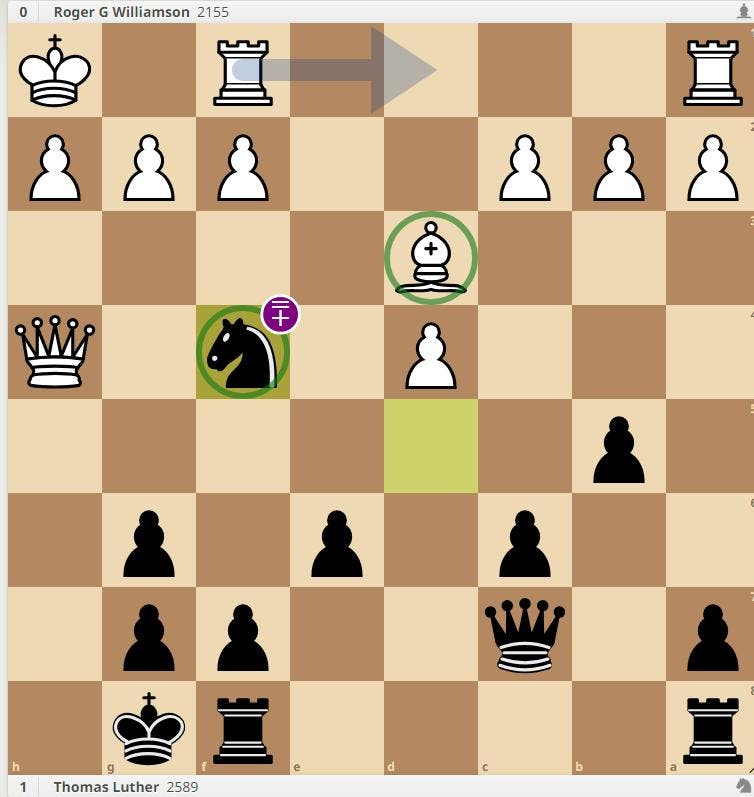

19. Be4 Rac8 20. Rad1 Rfd8 21. g3 Nd5 22. Qg5

White cannot simply exchange the knight for the bishop with 22. Bxd5? , as the resulting Carlsbad-like structure leaves white hobbled on the queenside and with no counterplay on the kingside.

White's queenside pawns will be smashed.

22.... b4!

The knight looks at the c3 square, anticipating an eventual white pawn move to support the d-pawn, directing the black b pawn to restrict it.

23. h4

What else does white have? He can't do much on the queenside, where he is restrained, so he may as well make futile attacking/expanding gestures on the kingside. That nothing white does seems to matter is due to the harmonizing power of the knight on d5.

23... Qb6

Black intends ...c5 and pressure on the c2 pawn and an eventual minority attack. The advanced black b-pawn restricts white's ability to do much about this.

24. Bf3

Anticipating ... Nf6 and an uncovered attack on the d-pawn. White can only play reactively.

24... Nf6

The knight has done what it can from d5, and now moves to increase the power of the black rook on d8.

25. Qe5 Rd7 26. Kg2

Again, such is the power of the knight on d5 as compared with the bishop on f3, white has nothing much constructive to do and must tread water in order not to drown. Here, instead of the game move 26... Rcd8, black was in position to play to play 26... c5!, targeting the weak c2 pawn:

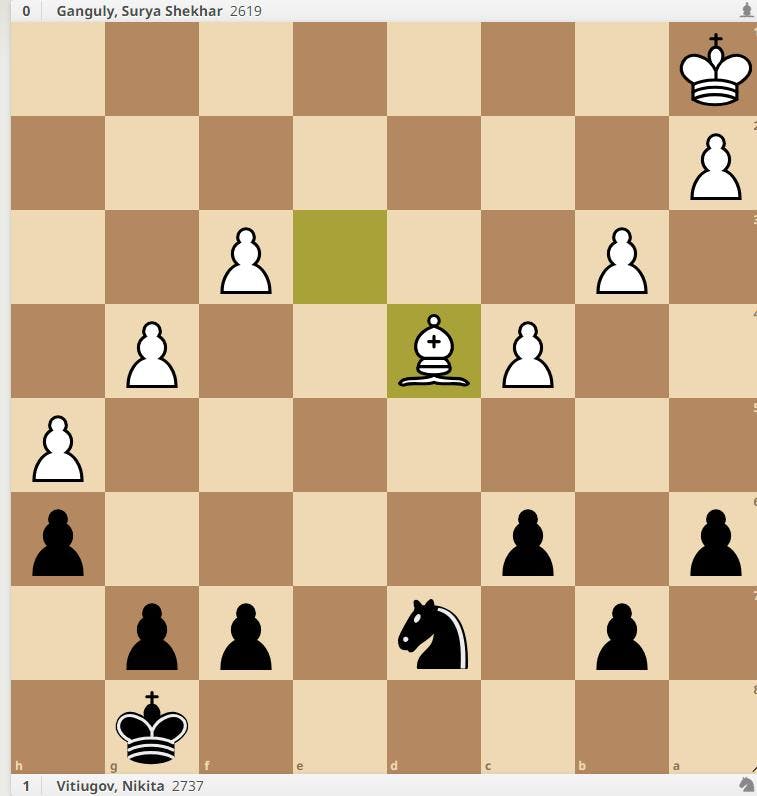

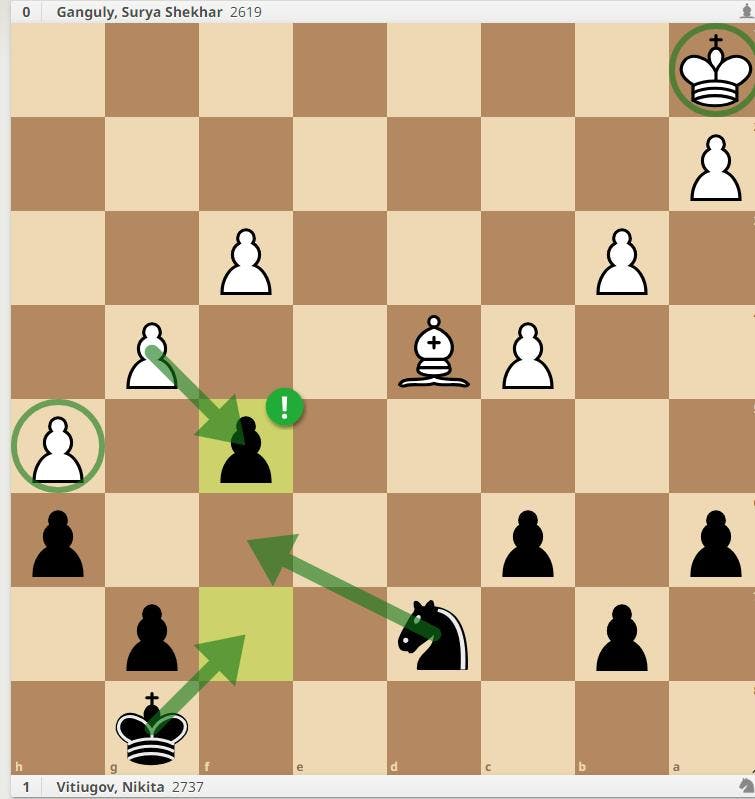

Surya Ganguly (2619) - Nikita Vitiugov (2737) Gibraltar, 2014

Conventional wisdom, which is to say general understanding, tells us that a bishop, being a long-range piece, is stronger than a knight in an ending where there are pawns on both sides of the board. Not always. There are complicating factors that make this general rule, well, a general rule, and as such rich with exceptions. Being the endgame, the placement of the respective kings is usually a major factor in assessing which side is better. But so too will be the knight's capacity, in combination with its own pawns, to disrupt the opponent's pawn structure.

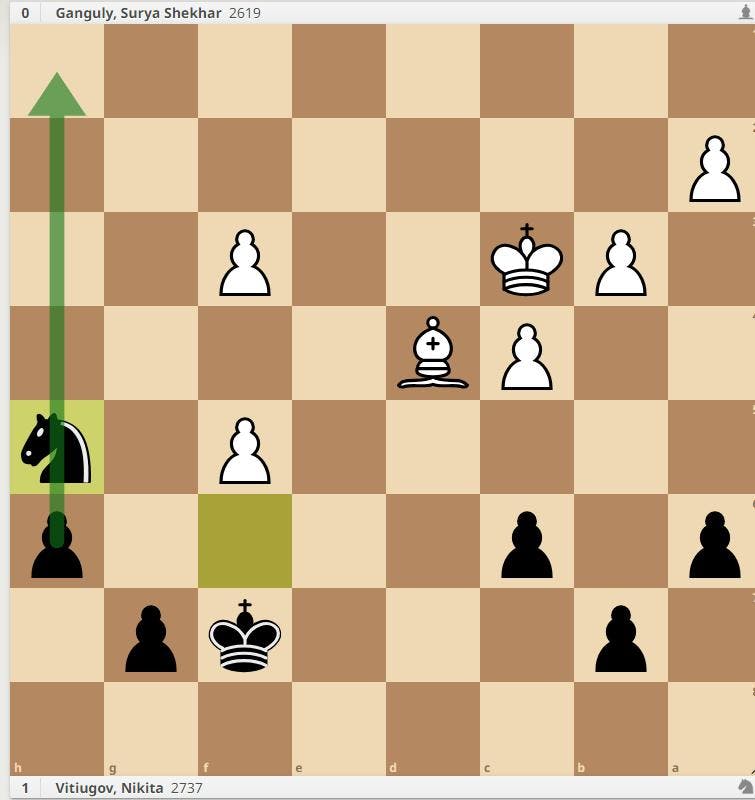

Black to play. The position is equal.

36... f5!

The position is still equal, but white's king is a long way from the action. Black is threatening to get amongst white's kingside pawns.

37. Kb2 Kf7 38. gxf5 Nf6 39. Nc3 Nxh5

Black now has an outside passed pawn. White's bishop makes the position equal, but, as with the last example, black is dictating terms, and it is white who has the problems to solve thanks to the knight, king, and passed pawn all working together.

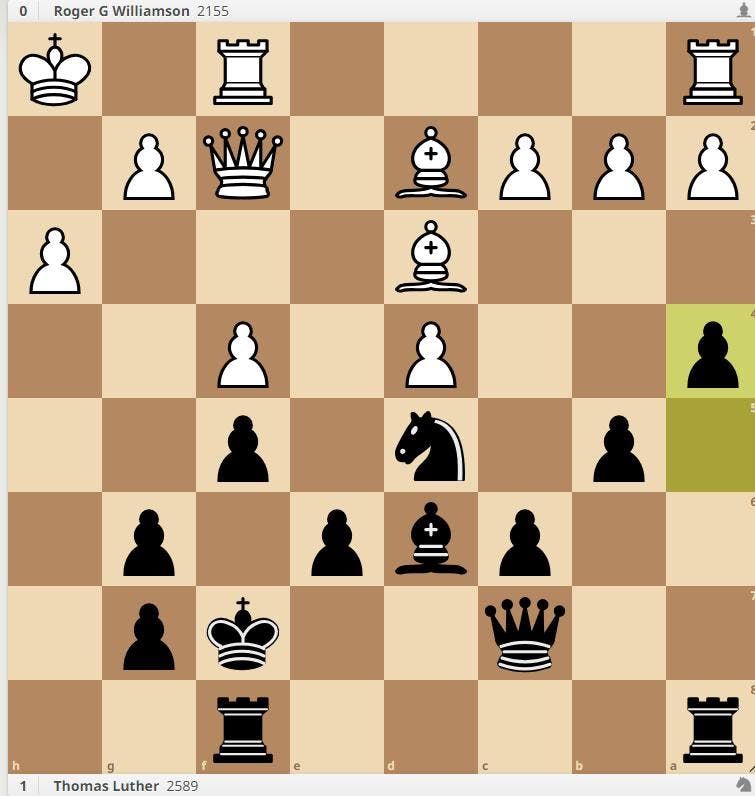

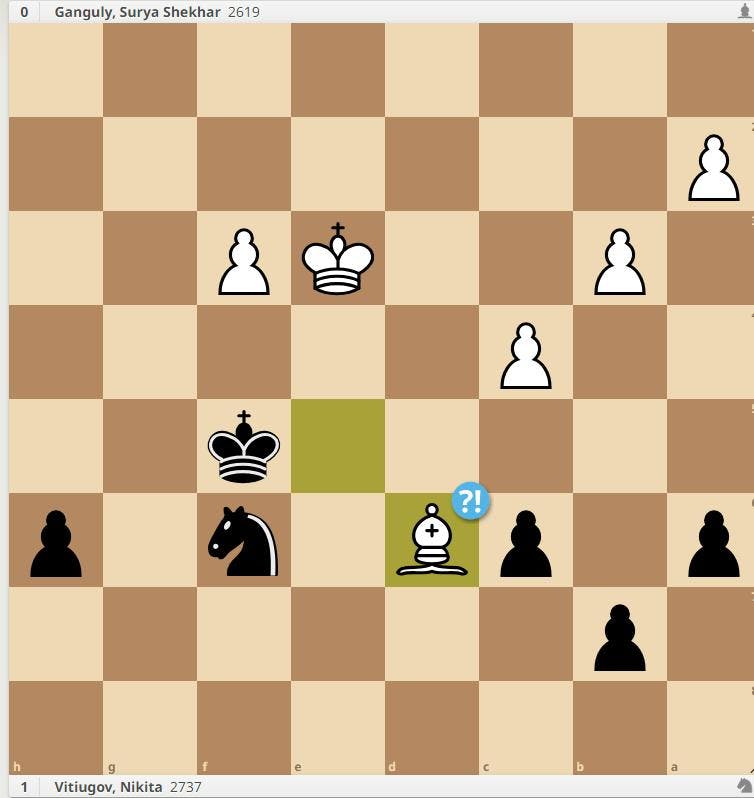

40. Be5 Nf6 41. Kd3 g6 42. fxg6+ Kxg6 43. Ke3 Kf5 44. Bd6?

According to the engine, this is an imprecision. Instead, 44. Bf4 h5 45. Ng3 keeps an equalizing eye on the h-pawn. But slight imprecisions are to be expected when you've been under pressure as white has.

44... h5 45. Kf2 Nh7 46. Kg3 Ng5 47. Bc5 Nf7 48. Bd4 Ne5 49. Be3 Nd3 50. Bd2 Ne5 51. Be3 h4+!

Liquidating to a clearly favourable ending for black.

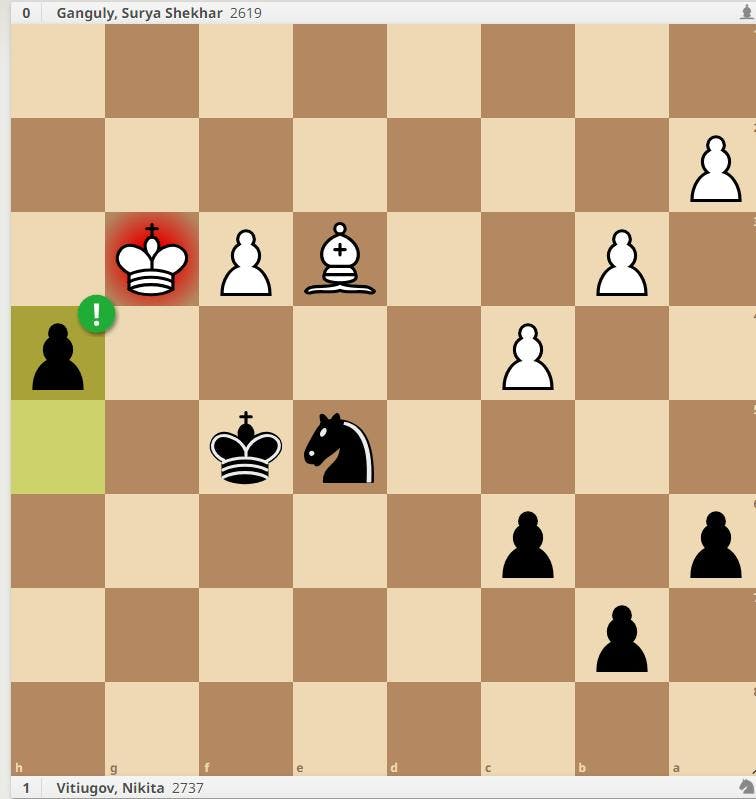

52. Kxh4 Nxf3+ 53. Kh5 Ne5

Now the position has resolved itself to one of pawns on one side of the board and white king cut off from play that wholly favours the black knight. Game over.

54. Bc1 Nd3 55. Bd2 Nc5 56. Bc1 Ne4 57. Bb2 Nf2 58. Kh6 Nd3 59. Ba3 c5 60. Kg7 Ke6 0-1

Efim Geller (2590) - Garry Kasparov (2545) Tbilisi, 1978

It's not all beautiful music, however. Sometimes the knight must exert itself to prove equal to the well-placed bishop. Let's see a young Kasparov's sophisticated handling of the Caro-Kann knight in a knight vs. bishop endgame resulting from a Classical Caro and the seemingly inevitable series of exchanges.

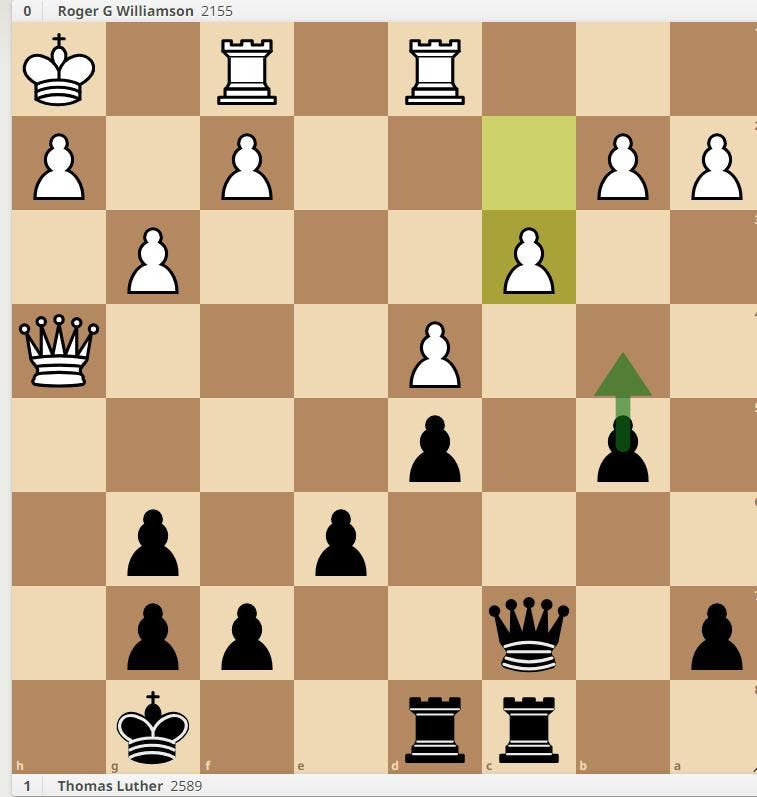

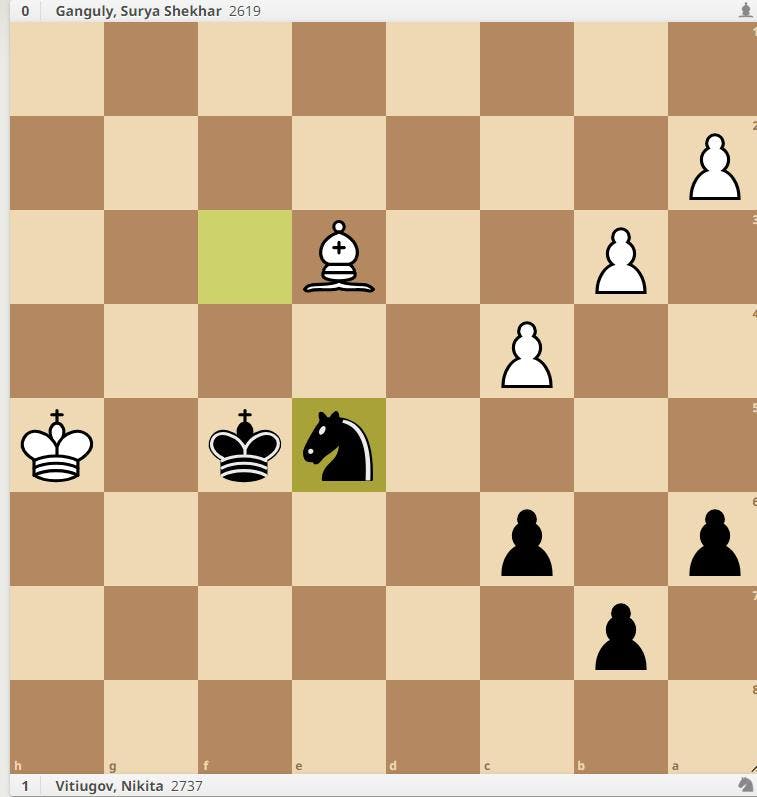

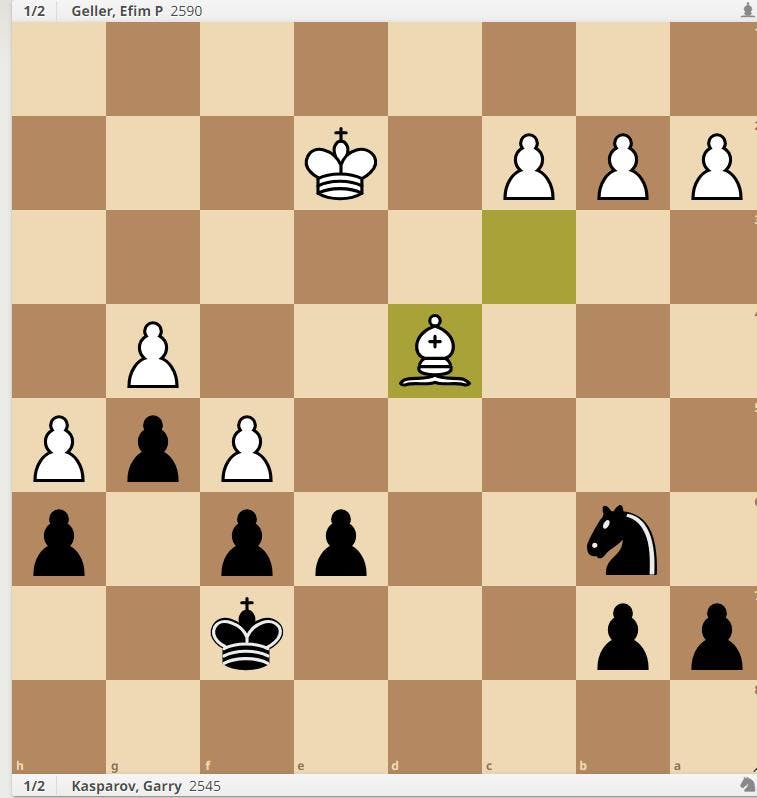

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nd2 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Bf5 5. Ng3 Bg6 6. h4 h6 7. Nf3 Nd7 8. h5 Bh7 9. Bd3 Bxd3 10. Qxd3 Qc7 11. Bd2 Ngf6 12. O-O-O e6 13. Ne4 O-O-O 14. g3 Nxe4 15. Qxe4 Be7 16. Kb1 Rhe8 17. Qe2 Bd6 18. Rhe1 Nf6 19. Ne5 c5 20. dxc5 Bxe5 21. Qxe5 Qxe5 22. Rxe5 Rd4 23. Kc1 Red8 24. f3 Nd7 25. Ree1 Nxc5 26. Bc3 Rxd1+ 27. Rxd1 Rxd1+ 28. Kxd1 f6 29. Bb4 Nd7 30. Ke2 Kd8 31. g4 Ke8 32. f4 Kf7 33. Bd2 g6 34. f5 g5 35. Bc3 Nb6 36. Bd4

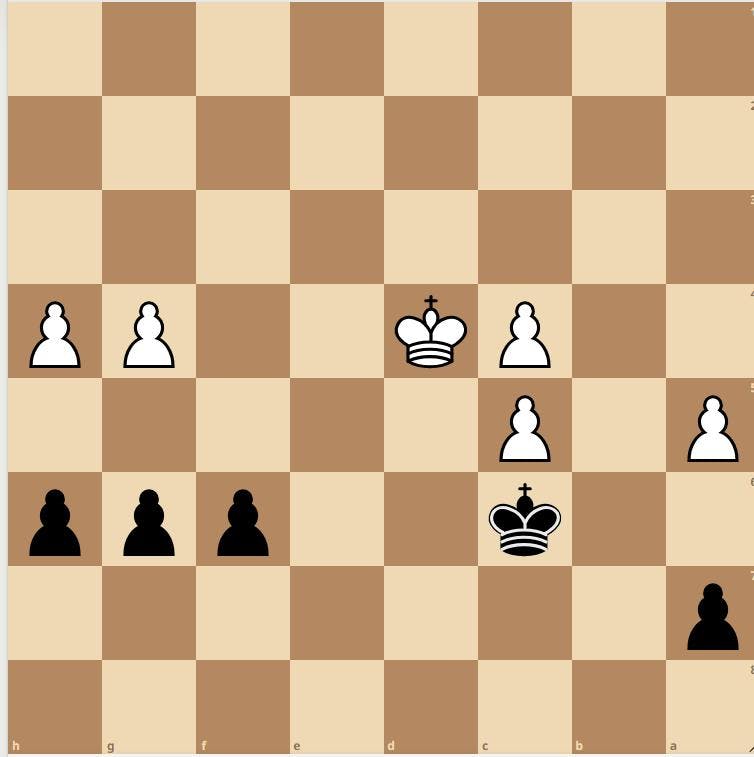

Black to move. Things look bad. White's queenside majority and centralised bishop suggest black is in some trouble. To begin to understand what Kasparov does next, here's a king and pawn ending that recently (almost) arose in a Merseyside league game:

White has the queenside majority, black the kingside. But white wins this ending with h5!

Fixing the weak black pawn on h6. White then wins by going after the h6 pawn with his king.

Back to the game. Kasparov played:

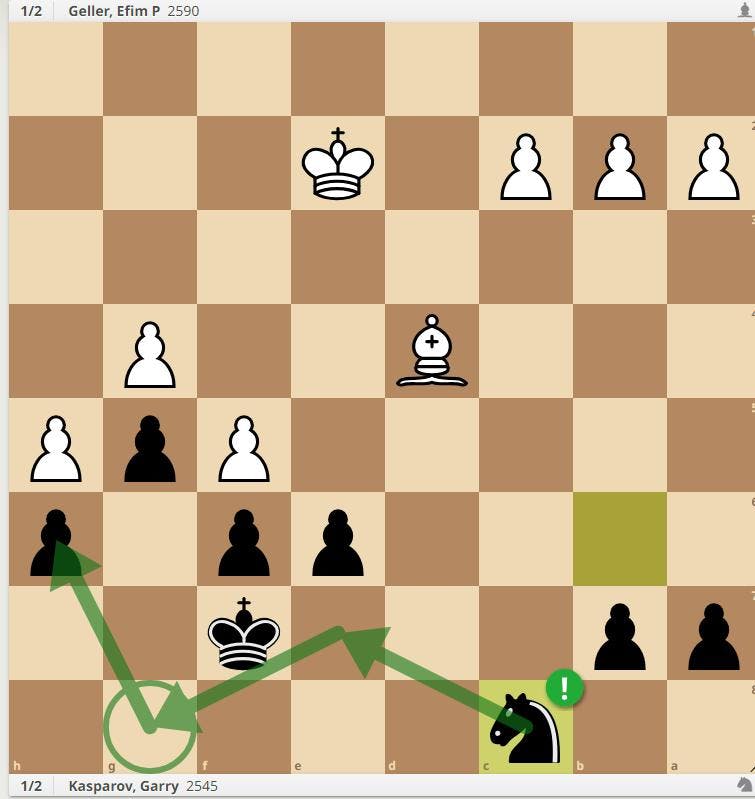

36... Nc8!

Intending to send the black knight all the way around to g8 to protect the weak pawn on h6.

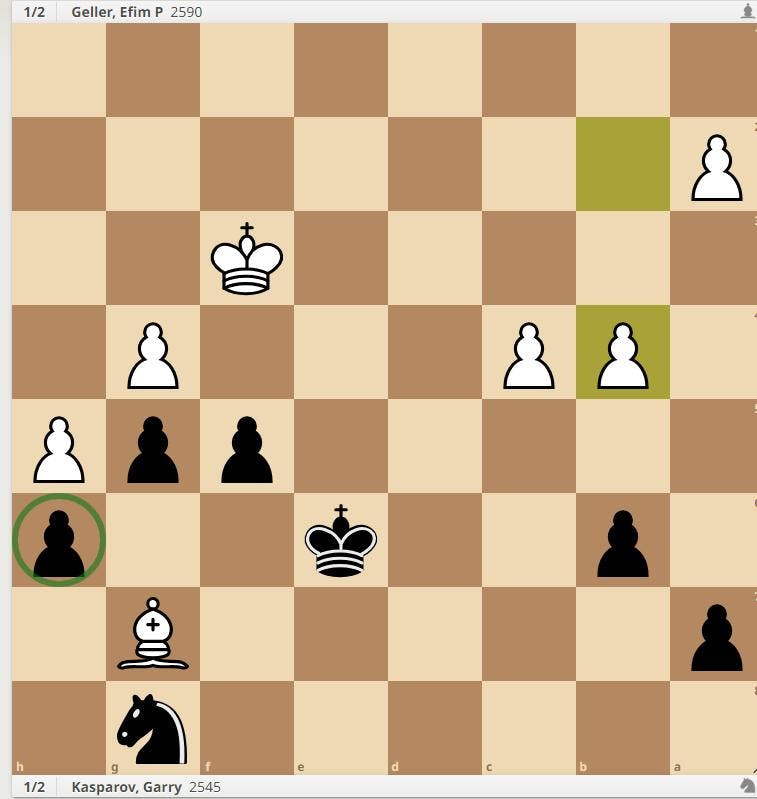

37. Kf3 b6 38. fxe6+ Kxe6 39. c4 Ne7 40. Bc3 f5 41. Bg7 Ng8 42. b4 1/2-1/2

At which point Geller, recognizing the black knight anchoring the kingside leaves the black king free to prevent white's queenside majority advancing, agreed to the draw.

How does white make progress? Try it for yourself. The knight on g8 is an unlikely hero, but it does indeed save the day.

If you're a Caro-Kann player (conductor, if you want to pursue the metaphor) you must make friends with your knight. Whether he leads from the front or from behind, he leads.