Baldrick: Oh, sir! Poor little Mildred the cat, what's he ever done to you?

Blackadder: It is the way of the world, Baldrick. The abused always kick downwards. I am annoyed, and so I kick the cat, the cat [loud squeak] pounces on the mouse, and finally, the mouse--

Baldrick: Argh!

Blackadder: --bites you on the behind.

Baldrick: And what do I do?

Blackadder: Nothing. You are last in God's great chain. Unless there's an earwig around here you'd like to victimize.

'Nob and Nobility', Blackadder the Third

The above dialogue, I suspect, is reminiscent of all our experiences of chess. There is a hierarchy in the game, and it feels fixed. What follows is an examination of why one particular aspect of that hierarchy exists - the lower rated player's urge to 'do something' against higher rated opponents - and how we can all hope to overcome it mid-game with a little self-awareness.

Unlike in Blackadder's retaliation-based vision of the universe, the higher rated player does not necessarily have to go on the offensive. Rather than attack like a cat or a sitcom mouse, they tend to wait like a Venus Fly Trap for you to walk into their jaws. The cure for this, unsurprisingly, is to avoid the temptation of the lure and instead force them to try and actively beat us, if they can, with their superior ability.

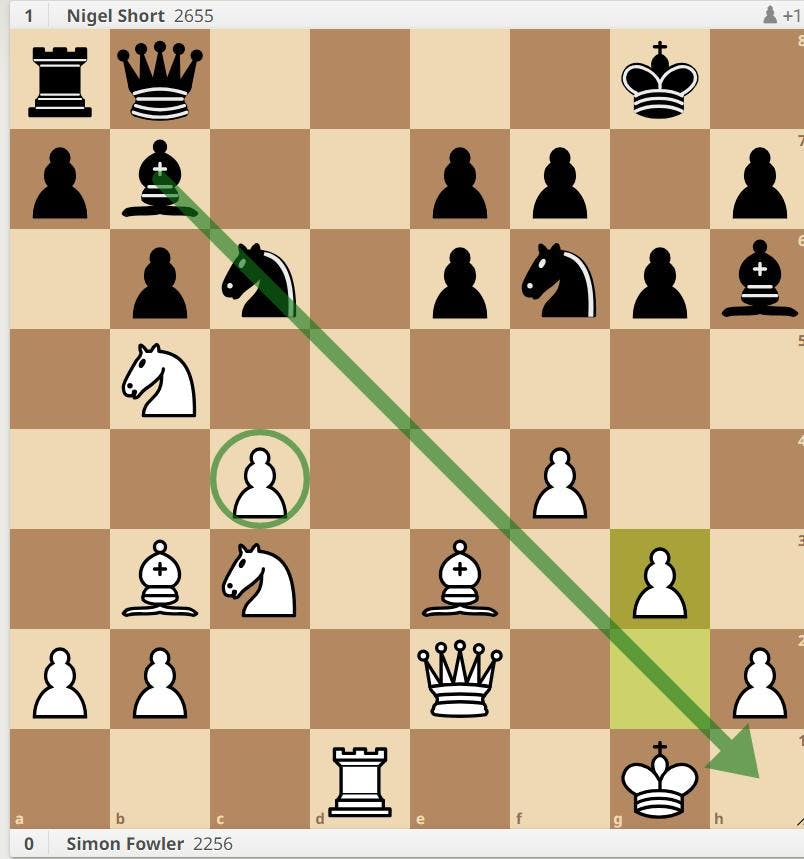

Simon Fowler (2256) - Nigel Short (2655) Liverpool, European Union Championships 2008

The following game was one I witnessed at the European Union Championships held in Liverpool in 2008. I then read an account of its analysis conducted by Nigel Short over that evening's dinner. As Short explained to his audience, white, a creditable amateur opponent, played a series of seemingly swashbuckling but rather awful moves early in the game for no reason other than he was playing Nigel Short, and was thus felt compelled to 'do something'.

1.e4 Nf6 2. e5 Nd5 3. Bc4 Nb6 4. Bb3 c5 5. Qe2 g6 6. e6??

It's easy to rationalise such a move. Perhaps black told himself he was 'shutting in black's bishop on c8'. Add to which, it's a 'pawn sacrifice, and only strong players are prepared to play those.' Finally, you're playing Nigel Short, so you're probably going to lose, 'so you should at least go down fighting.' Nobody can say you didn't give the great player a game - or at least something to think about.

Unfortunately, away from these parentheticals and back in the game itself, 6.e6 is just a free pawn for black. Had Simon been playing someone rated 2400, say, then he would no doubt have realised that and not played 6. e6. Such is the psychological pressure on the substantially lower rated player, the little voice that says 'do something' drowns out the usually dominant one that says 'don't be silly'.

6... dxe6 7. Nc3 Bg7 8. Ne4 Qc7 9. d3 Nd5 10. c4?

Another gunslinger-type move. White's position was already bad, but now it's beyond hope. That pawn on c4 will soon become a weakness when white pushes through d4 to stop both the d3 pawn and the d4 square being weak. Again, I strongly doubt white would have played such a move against anyone rated lower, the same, or slightly higher than himself.

Nf6 11. Nc3 O-O 12. Nf3 Nc6 13. Be3 b6 14. d4 cxd4 15. Nxd4 Bb7 16. O-O Rfd8 17. Ndb5 Qe5

Pure provocation. This is not necessarily objectively the best option. It's designed to force white to yet again 'do something' and play another weakening move.

18. f4?

Which he does (though, admittedly, it's hard to see what white could plausibly do to improve his position).

Qb8 19. Rad1 Rxd1 20. Rxd1 Bh6! 21. g3

And now black has an overwhelming advantage. Thanks to the pressure of the rating disparity, and his resulting kamikaze bravado, white has a weak pawn at c4 a wide-open king. (He's also a pawn down from the original sacrifice, but with things as otherwise bad as they are what does that even matter?)

21... e5

Black merely has to open the position and white's weaknesses tell.

22. Nd5 exf4 23. Bc1 Qf8 24. Nxf6+ exf6 25. Nd6 Na5 26. Bxf4 Bxf4 27. gxf4 Bc6 28. Ne4 Kg7 29. Qd3 Qe7 30. Nd6 Nb7 31. Nxb7 Bxb7 32. Kf1 Bc6 33. Re1 Qc7 34. Qe3 Re8 35. Qf2 Be4 36. Qd2 Rd8 37. Qf2 f5 38. Re3 Rd4 39. Rc3 Bd3+ 0-1

How hard did white have to work for that win? Not very. He was simply able to harness the psychological advantage that being Nigel Short gave him over his opponent. Perhaps we should see the 'do something' phenomenon as a form of panic? Or an act of unconscious defeatism?

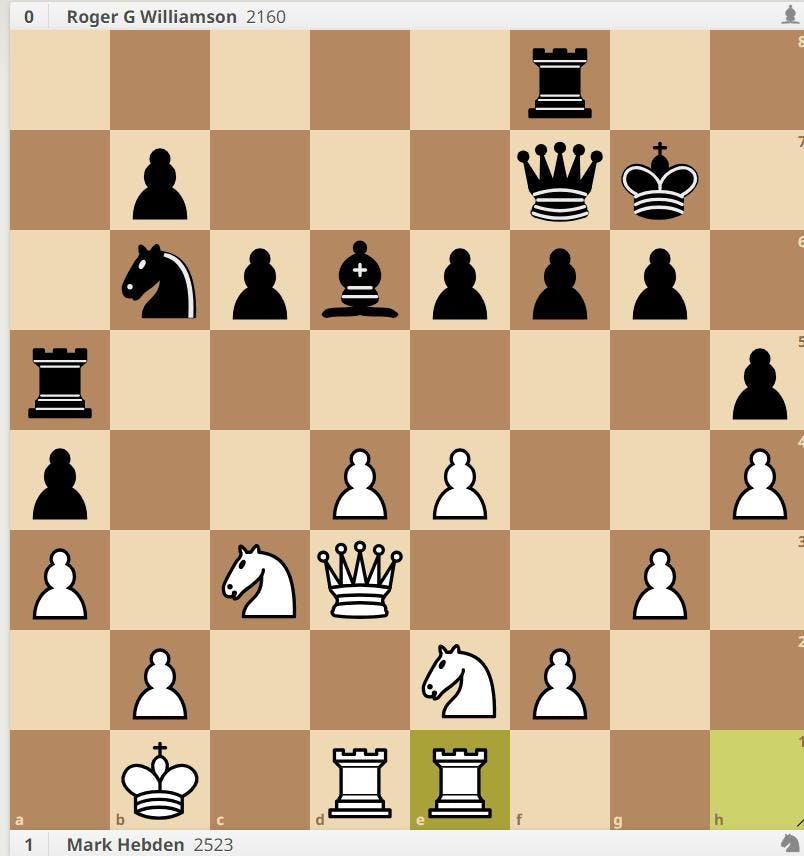

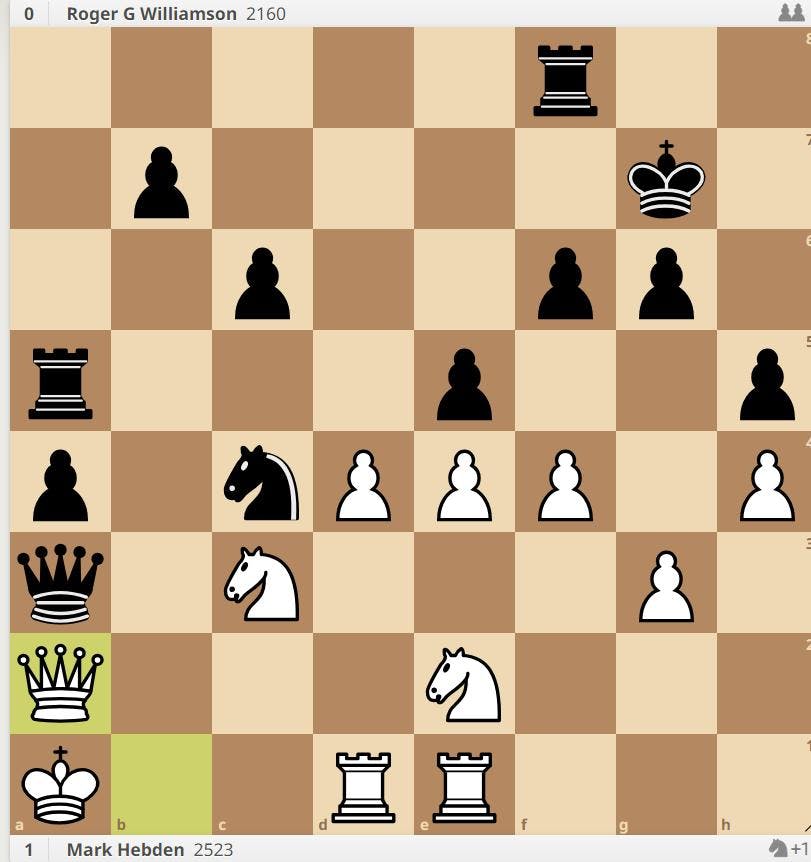

Mark Hebden (2523) - Roger Williamson (2160) London, London Chess Classic Open 2014

I said it was easy for a creditable amateur to rationalise such moves as 6. e6?? and 10. c4?, no matter they must innately know them to be mistakes. Now I'm going to prove it myself at a slightly lower level.

After 20. Rhe1. Black to play

Black (me) had ridden his luck so far and escaped from a dodgy early middlegame into a more-or-less equal position. 20... Rd8 would have resulted in an acceptable position. Alas, I saw that I could sacrifice on a3 and then deliver a check on b3. Where normally I would never have dreamed of 'doing something' so daft, here, last round in a nine round open, against a GM, such a futile sacrifice with no follow-up must win, surely?!

20... e5?

Phase one of a two move self-destruction initiated.

21. f4 Bxa3??

Self-destruction complete.

22. ba Qb3+ 23. Ka1 Nc4 24. Qb1 Qxa3+ 25. Qa2

And black's attack was over almost as soon as it started. The game carried on a while longer before I resigned, if only because I wanted to obscure the immediate memory of my act of hara-kiri. Upon my resignation, Hebden asked me why I'd done what I did. But before I could think of a plausible alternative to the truth (a tall order), he answered for me: 'Glory!' - which could also have been the title for this article.

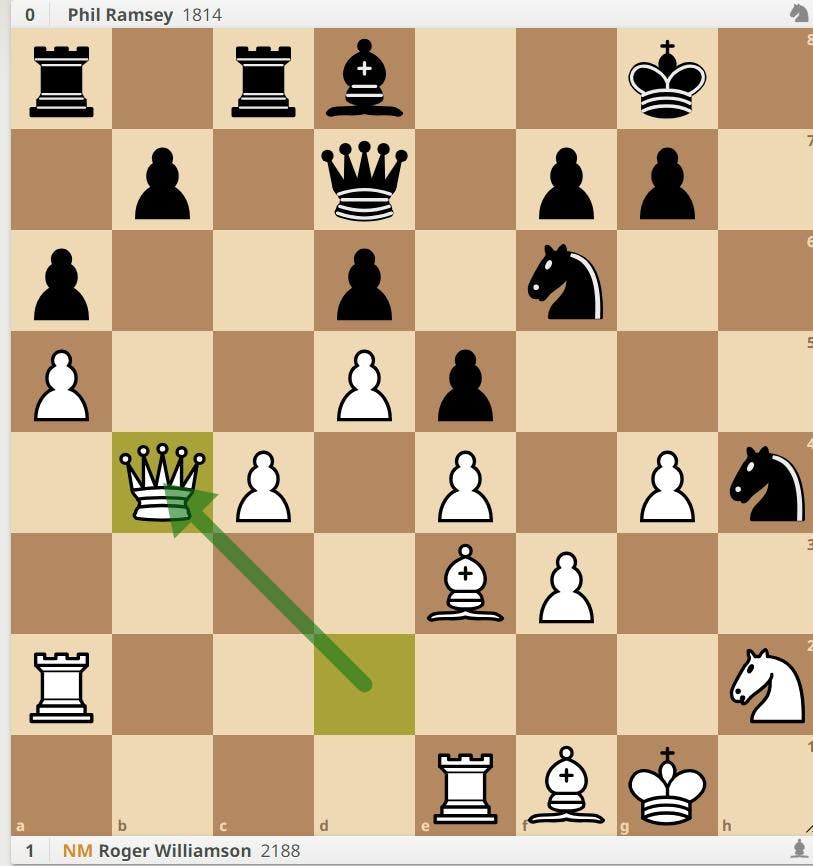

Just as in Blackadder, just as it goes between 2500 Grandmaster and 2100 amateur, so it goes between a 2188 and an 1814.

Roger Williamson (2188) - Phil Ramsey (1814) Liverpool, Atticus Open 2023

After 25. Qxb4. Black to play.

Versed now in the dark art of provoking the lower rated player into committing an act of romantic self-harm, white has sent his queen on a jaunt to pressure black's creaky queenside, largely in the hope black will give in to temptation and sacrifice (blunder) the knight on f3. White was ahead on the clock, but black had more than enough time (a few minutes plus increment) to find the resource 25... Nh7! which gives him equality. However, who could resist instead doing something?

25... Nxf3+??

Notable in both this failed attack and the one in the previous game is the allure of meaningless checks. (It's worth noting for posterity that one of the spectators let out a barely suppressed 'yes!' of approval when this move landed.)

26. Nxf3 Qxg4+ 27. Bg2 Nxe4 28. c5!

The Gerry-built nature of black's attack is revealed in its crumbling. Even if I didn't exactly play the best moves from there, black inevitably had to resign shortly after. In the post-mortem Phil told me just what I'd expected to hear regarding 25... Nxf3+: owing to the rating disparity between us, and his deficit on the clock, he had had to 'do something'.

The bad news is that chess is like Blackadder's universe in one respect. As anyone who has tried to substantially improve their rating beyond a certain age can testify, the chess hierarchy is, sadly, more-or-less fixed. But this is a macro view that defies the micro possibilities of each individual game that makes the game itself attractive. If we, the lower rated player, could stop giving in to the temptation to 'do something' in search of 'Glory!', then at the very least the mouse would have to work hard to bite Baldrick. Who knows, maybe the mouse might then eventually give up trying to bite - or better yet, Baldrick see a real opportunity to bite back - and the universe not seem such a harsh place after all.

If only there was a maxim I could fashion from all that wisdom. Howabout: 'Don't do something until there is something to do'?1